America’s Good Culture War

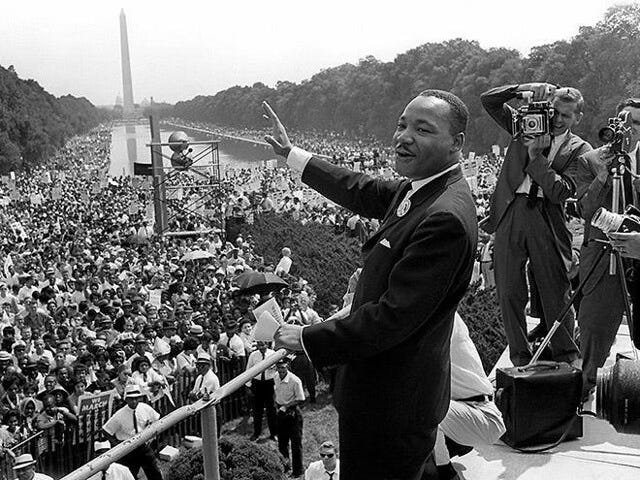

Reflecting on a tribute to Martin Luther King Jr.

Civic Fields, a perennial Thursday publication, is coming out on Monday this week with a short reflection on the life and work of Martin Luther King. I hope it provides a bit of food for thought on this important date in the national calendar. - Ned

On October 18, 2007 Professor William J. Stuntz of Harvard Law School stood before an audience at his alma mater, the University of Virginia Law School. It was not MLK Day, not even close. Nevertheless, in a talk called “Law and Grace,” Stuntz used his academic homecoming to reflect on the life and work of Martin Luther King. It is a reflection that a good friend in law enforcement shared with me, and one I’d like to share with you here. Recalling King and the Civil Rights movement, Stuntz spoke of a different kind of culture war, a good culture war.

Given everything that’s happened since, October 2007 seems like a century ago. George W. Bush was tumbling toward his final year in the White House. John McCain would be the heir ascendent in the Republican Party. And on the side of the Democrats, a Hawaii-born black upstart senator from Illinois named Barack Hussein Obama II was running against the entitled Hillary Clinton for the presidential nomination.

Perhaps this is why Prof. Stuntz spoke that day as if an old era was passing and a new one was being born. But rather than speak with hope, his tone that day was largely one of regret. He began,

Two metaphorical wars have defined American politics and American law over the last generation: the culture war and the war on crime—especially, drug crime. Aside from the fact that these two non-wars have been misnamed, they seem to have little in common. One is about abortion and gay rights, the other is about crack and crystal meth. The key actors in the first are Supreme Court Justices and religious right politicians; the key actors in the second are big-city prosecutors and the members of urban gangs. There doesn’t seem to be much overlap here. Actually, I think there is a lot of overlap.

Stuntz explained that both the culture war and the war on crime were strongly supported by theologically conservative Protestants in America, and in both “wars” the results were quite inimical to what one would hope from the political mobilization of legions of people who call themselves Christians. Instead of producing care for the vulnerable and grace toward the struggling, the political mobilization of conservative Christians had produced a regime that thinks of law and government first and foremost as forces meant to “condemn and punish moral wrongs.”

As Stuntz looked out on the country in 2007, he saw a nation bent on righteous violence and punitive solutions to social problems. Stuntz—who self-identified as an evangelical Christian and member of a theologically conservative Protestant church—largely blamed conservative Christians like himself for the flooding of prisons, the growing violence of policing, and indeed the adoption of “war” as a metaphor for struggles against crime and vice.

Little could he imagine 2026.

Stuntz tried to offer some explanations for what had gone so terribly wrong: mistaking political power for social power, believing that law and government have the power to shape culture, an implicit moral paternalism, a retreat among religious types from neighborly love in favor of policy positions, and, not the least, a fundamental conflation among many American Christians (in fact a fundamental confusion) between being Christian and being American.

But, again, Stuntz spoke as though the long era of the overlapping culture war and the war on crime were coming to an end. New horizons were opening up in American life. The country had the opportunity to try on a different kind of politics, and Christians in the country an opportunity to recall a different ethic. Of course, he was wrong, woefully so. But he can be forgiven for holding out the hope. I recall vividly the sense of national optimism that Obama was generating in 2007. I recall the feeling that after years of war—including literal wars overseas—the country seemed primed for peace at home and abroad.

But in fact, Stuntz was not speaking of a Pollyanna new era in American life. Instead, he was looking forward to a new culture war, a different kind of culture war, one premised on the hard work of relationship and reconciliation rather than retribution.

For this, he summoned the memory of King and the Civil Rights movement. “King fought and bled and died for the right to have a relationship with those who refused relationship with him. He did not seek to punish, though he had every excuse and every right to seek precisely that. He wanted his enemies’ embrace.”

Such an ethic, Stuntz argued, was at the heart of “America’s Good Culture War.”

I believe King’s movement was America’s Good Culture War, one that was fought as such battles ought to be: aggressively and passionately and with deep commitment to principle, and yet also with love for those with whom the movement did battle. Call it the marriage of law and grace. Legal change helped produce social and cultural change—not by locking up evildoers, but by building the beginnings of an integrated national community.

Abraham Lincoln, the historical leader whom King most resembles, would have understood. Lincoln fought a terribly bloody war . . . and yet, as hard as he fought, Lincoln could not bring himself to hate those he fought. They are our countrymen, he liked to say; we should approach them “[w]ith malice toward none; with charity for all”—famous words that define the spirit of the one who spoke them. That spirit, and King’s spirit, have been too little evident in the culture wars of the recent past.

Some might wish for an American future free of culture wars. I do not; I think these battles are worth fighting. But I do wish for good wars: the kind King fought—the kind in which we love our enemies, and fight for the chance to embrace them.

Good words for today, and every day to come this fateful year.