Between Heroes and Villains

A walk along Boston’s Freedom Trail, Part 1

Why do some places make visitors “tourists” and other places, well, just let them be visitors? Is this just a factor of branding? The amount of tourists per year? How cheap flights are? Matt Pitchford, who teaches at Northeastern University, reflects on why people visiting Boston don’t want to be “tourists”—they just want to be in Boston, part of the place. This is in sharp contrast, of course, to Las Vegas. At core of Matt’s reflection here, which he will carry on over the next few weeks, are questions about not just visiting, but belonging. They are questions worth reflecting on for all of us as we think about what it means to belong to a town, a city, a country, a globe. - Ned

Boston is a city of heroes and villains, where most of us live comfortably in the capacious space in between. I moved here in 2021 to take a postdoctoral post at Northeastern University. Last year, that position turned into a permanent position. So, I am on the road to becoming a Bostonian. Far from having no complaints, I am downright thrilled about it.

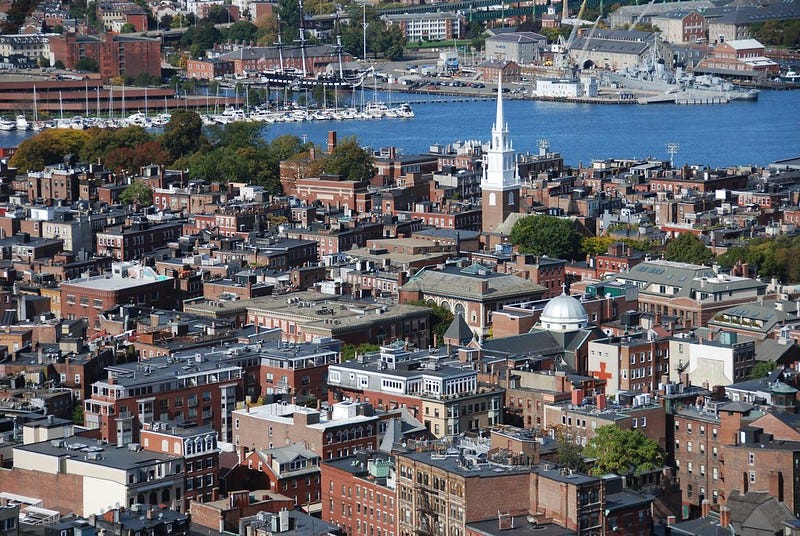

I love Boston. I love the energy of the city, love the history, and love exploring its oddly laid out streets. It’s a city of nooks and crannies that tell stories of crooks and heroes. Growing up in the Pacific Northwest, I have found Boston familiar, if slightly tilted: the ocean is right there, but it’s the Atlantic. The city is full of trees, but they’re elm and maple instead of pine and firs. And like where I grew up, history is everywhere. In Boston, history is not just in the neighborhood: it is the neighborhood.

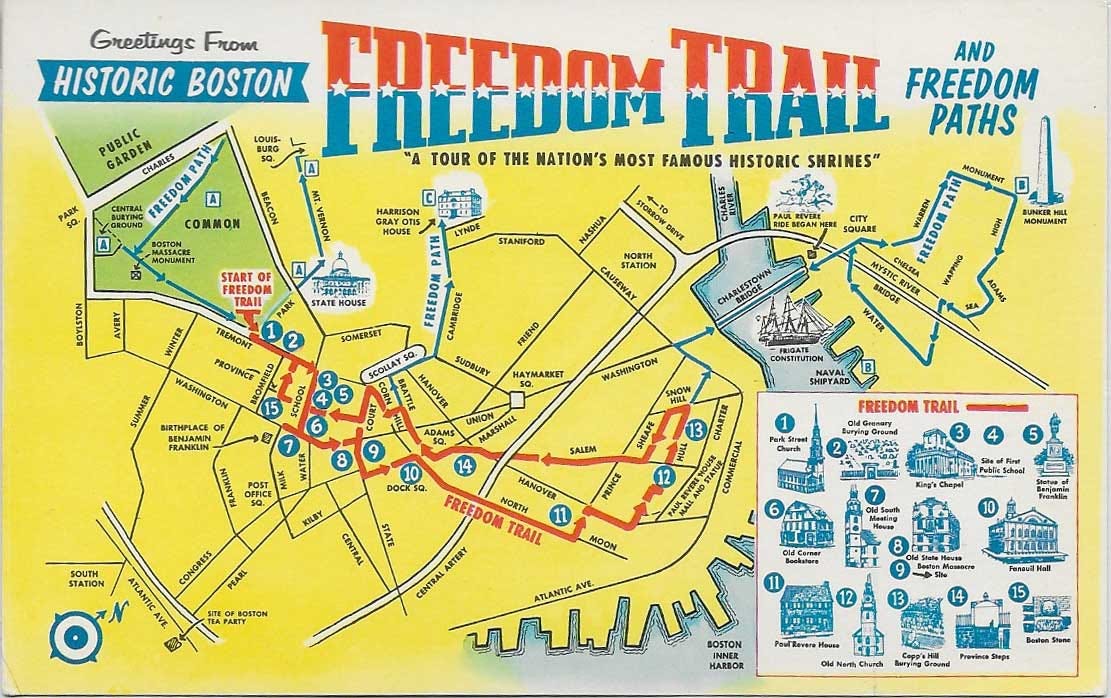

One of my favorite things to do as a still new Bostonian is to take visitors along the Freedom Trail. My family jokes that the only thing my tour is missing is a tricorn hat and period clothing. But my tour isn’t only about seeing the historic Revolutionary era sites, it’s also about how the city has grown, changed, and what it means to belong.

I am going to take Civic Fields on a little field trip along Boston’s Freedom Trail, using it to reflect not just on the city and its history, but also on what it means to learn to live in the place you are and learn to love it, be part of it. I admit, it may be easier to do that in Boston than in some other places, but every place has its Freedom Trail or equivalent—sites of stories, struggles, heroics, and, yes, some villainy. Often these places are hidden. We have to dig them up. Boston has the advantage of having so many of these sites right there for the taking.

We’ll start with Charlestown.

Charlestown: When I venture out along the Freedom Trail, I like to begin further out and work my way back to downtown. We take the Orange Line metro out to Community College in Charlestown, the first stop north of the Charles River. Charlestown was first laid out in 1629, predating the founding of Boston. As ships got bigger, Boston’s deeper harbor became the busier port, but Charlestown remained a center of ship building. With its proximity to the Naval Yard and related industry, for a long time Charlestown was a working-class neighborhood full of carpenters and rope makers, and later welders and iron workers. Since the Yard was closed in 1974, Charlestown has been gentrified. (Today a one-bedroom apartment will cost you between $2500 and $3500 a month, a condo costs $800,000, and a house—even a tiny one—will be listed for over a million dollars.)

Ben Affleck’s movie The Town starts with the claim that there are more bank robbers from Charlestown than any other place in the United States. The numbers are dubious, but it is true that Boston has many historical connections to organized crime. Boston crime movies are their own little niche: Black Mass, Mystic River, Boondock Saints, Gone Baby Gone, Edge of Darkness, and The Departed. The most infamous crime in these parts in the last fifty years was the great 1989 heist at Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum of Rembrandt’s only seascape, Storm on the Sea of Galilee, along with artworks by Vermeer and Degas (the museum is in Back Bay, not Charlestown). There’s still a $10 million dollar reward for information on the stolen art, but there’s been no solid leads. Most likely, the artworks are not in some billionaire’s private collection, but are being held by the mob for collateral or as a bargaining chip for a reduced prison sentence. After all, there is historical precedent for this.

People here tout even tangential connections to the history of organized crime, part clout and part small talk. The guy who came to fix our dishwasher bragged that his family used to live next to Whitey Bulger. A security guard I met insisted that Whitey’s politician brother, William, was a really nice guy who remembered everyone’s name. There are mob tours that you can take, right next to the ghost tours.

It's odd but true that a history of organized crime can contribute to a pride of place. Perhaps one positive function of fame is to cleanse and preserve otherwise insidious histories. I don’t get the sense that anyone around here actually wants to go back to the time when the Irish mob ran guns for the IRA. But they prize the stories of having grown up next to celebrities. The image of a gangster is seen as a bit cool.

Bunker Hill Monument: From Charlestown we go to the Bunker Hill Monument. The famous Battle of Bunker Hill took place on June 17, 1775, just after the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Bunker Hill had a commanding view of Boston Harbor, and so the British could not simply let the revolutionaries occupy the heights and control access into Boston with their artillery. After a pitched battle, which included the famous command “don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes,” the revolutionary army was forced to retreat. Technically, the battle was a loss for the Americans. But as General Nathan Greene later said, “I wish I could sell them another hill at that price.” For a scrappy group of revolutionaries to cause such grievous harm to the greatest military in the world was a great boon to morale. Scrappy is still a thing today in Boston. You see it when David Ortiz, “Big Papi” shouts “this is our fucking city” at Fenway after the Boston Marathon bombing. You see it when people confront ICE officers in the streets.

A jaunt past the Training Field, where militia members drilled in the 1640s, takes us from Bunker Hill to the USS Constitution. The USS Constitution was commissioned in the 1794 Naval Act as the flagship of five ships to be built for the nascent U.S. Navy. She first saw action against the Barbary Pirates, America’s first war to protect American interests abroad, and fought in the War of 1812. It was during this war that she earned her nickname, “Old Ironsides.” During a protracted battle against the HMS Guerriere, the Constitution was raked by a cannon salvo from the British ship. No one knows for sure the provenance, but apparently one overly eager shipman surveyed the negligible damage to the hull and put up a shout: “Huzzah! Her sides are made of iron!” It is confirmed, however, that after the battle they found cannonballs embedded in the sides of the ship, unable to penetrate within. The USS Constitution is still a commissioned ship in the US Navy, and the oldest ship by far in any Navy in the world. She maintains her commissioned status by sailing one nautical mile every year, on July 4th, as a part of Boston’s patriotic celebrations.

The North End: Crossing over the Charlestown Bridge puts you in the North End, the historically Italian neighborhood. Italian immigrants were not treated well in the 1800s and were pushed into what was effectively a slum in the northernmost portion of the city. It was industrial and run down and people regularly died in industrial accidents—as when 2.3 million gallons of boiling molasses used for making booze burst out of a holding tank and killed 21 people. Today, the North End is an entirely charming historic neighborhood with droves of Italian restaurants, delis, and bakeries.

The North End brings us to the Old North Church. Here’s where we find heroic stories. It was from the Old North Church’s steeple that the deacon lit the famous lanterns, “one if by land, two if by sea,” that set Paul Revere on his ride on the eve of the battles of Lexington and Concord. Longfellow would later lionize the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

He said to his friend, “If the British march

By land or sea from the town to-night,

Hang a lantern aloft in the belfry arch

Of the North Church tower as a signal light, —”

History, unsurprisingly, had a different tale to tell than this one. First, Paul Revere was only one of a dozen riders who went out to spread the word. And he would not have been shouting “the British are coming!” Such an exclamation would have made little sense; for the revolutionaries were British!

Paul Revere was the real deal, though. And his house is the oldest still-standing building in Boston. It was built around 1680, and Revere’s silver smithing shop was next door. Now it’s a museum, but I’ve never been inside. Everyone has told me it isn’t worth the cost of entry, “it’s just an old house.” But the little park across the street is where I like to bring folks to eat cannoli. There’s a longstanding rivalry between Mike’s Pastry and Modern Pastry Shop, both are cash only, only a block or two apart, and always have lines out the door. I prefer Modern, personally, so that’s where I bring people to try the cannoli. There’s never any seating, so Revere Park it is.

The North End is itself a tourist destination filled with local color and approximately one billion Italian restaurants, but how it was transformed into the cultural center it is today is because of two historical developments. First, being Italian was subsumed into a larger category of being white. Rather than staying as what was effectively an over-industrialized, under-serviced ghetto, the neighborhood became more desirable to live and invest in. Second, the North End was saved by infrastructural redevelopment.

In 2007, Boston completed the “Big Dig.” Interstate 93 is a major highway that now runs underneath Boston in a series of tunnels. Prior to 1982, the elevated highway used to bifurcate the city. The North End was effectively cut off from downtown, and would have died a slow, noisy, and polluted death like so many other neighborhoods in other cities when the highway comes through. But instead, and fortunately, it is a pleasant, greenery filled walk or easy metro ride from downtown to the North End. Boston had the first metro system in the U.S., which was first pulled by horses between stops. Now the ridership on the “T” is 800,000 people every weekday. Even with this relatively robust public transportation (for an American city), traffic snarls every day at rush hour.

We’ll proceed further along the Freedom Trail next week, but here as I sit at Revere Park with you, I want to conclude by reflecting just a bit on what’s made the North End a tourist destination and what it means to be a visitor here, for it also tells us something about what it means to be citizen and a resident here.

It’s striking to me that this is a place where people don’t want to look like tourists. This is not Las Vegas or Disney World. Safety may be part of the explanation. (Growing up I always heard that when in the city you need “situational awareness” and should put your wallet in your front pocket so you can’t be pick-pocketed too easily.) But I think the bigger drive is a desire for an authentic kind of experience that the history of this place invites. Much of Boston invites this: Where do the locals go? What do they enjoy? What hidden gems are there? Finding a cool spot off the well-worn Trail is a pleasurable experience, and there are plenty of tourist websites that tout themselves as being able to do exactly that. Like a lot of places, I guess, when you come to Boston you don’t want to be a tourist; you want to be, even for a moment, a Bostonian.

Certain cities invite this. Others don’t. Histories of urban development have a lot to do with what a city invites, in large part because they can preserve or erase histories. The Big Dig allowed the North End to survive and thrive. And I can’t help but feel that there could have been more neighborhoods like the North End if things had been different. Take, in contrast, Seaport. Seaport is the newest neighborhood in Boston, literally wrested from the ocean using dirt from the Big Dig and other projects. It’s full of glass high-rises and fancy restaurants. They have an Alamo Draft House, a big convention center, several music venues, and a variety of beer gardens. But they decided not to be served by the Metro system. So Seaport is hard to get to using public transportation and even harder to live in, unless you have tech money. This isn’t to say that Seaport isn’t nice, just that in a city defined by neighborhoods it ends up feeling the most generic or sterile. Hopefully its identity will grow and change with time.

Matt Pitchford is an Assistant Teaching Professor in Communication Studies and director of the public speaking program at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts. Originally from Washington State, he has slowly been working his way east after living in Illinois for nearly 10 years. He loves cooking, eating oysters, and growing tomatoes.