Civil Rights Are Never Enough

A Juneteenth reflection on the political thought of Martin R. Delany

It’s Juneteenth. Today marks the 160th anniversary of the day Union troops showed up in Galveston, Texas, some two years after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, to liberate the quarter-million blacks still enslaved in the state. The liberation of another is the liberation of all. The purpose of freedom is to help someone else be free.

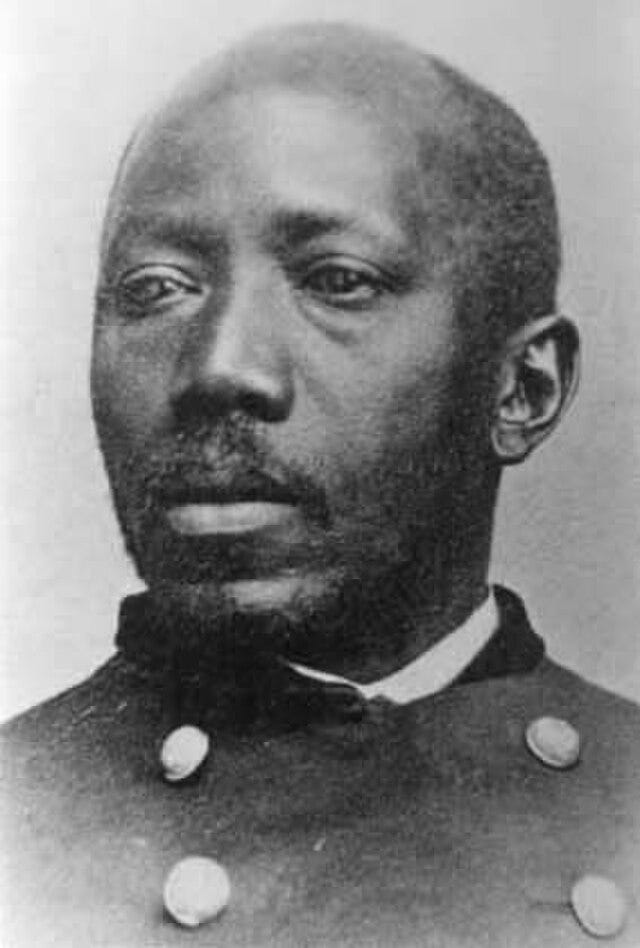

I would invite you to celebrate Juneteenth with me by sitting for a bit with Martin R. Delany (1812-1885), a prominent black leader in the abolitionist movement and an active, if controversial voice during Reconstruction.

I first read about Delany a couple of years ago while reading Melvin Rogers’ The Darkened Light of Faith: Race, Democracy, and Freedom in African American Political Thought, a book that I am particularly drawn to because of the ways in which it shows the connections of the black freedom movement of the 19th century to the concepts and tenets of political republicanism that I have been discussing on and off here at Civic Fields.

The youngest of seven siblings, Martin Delany was born in 1812 as a “free” black in Charlestown, Virginia (now West Virginia). To be “free born” then was no small thing compared to being born a slave, but it did little to free him from a life of persistent racism, harassment, and dehumanization.

As a young man, Delany made his way to Pittsburgh, an epicenter at the time of black activism and abolitionism. There, he helped found and run several educational and moral reform societies. He also took to journalism. In the 1840s, he founded the Pittsburgh Mystery, an abolitionist publication that, while short-lived, gained a significant readership well beyond Pennsylvania. Hence, in 1847, Frederick Douglass visited Delany in Pittsburgh and asked him to help him found a new newspaper, the now-famous North Star, which would rival William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator in the abolitionist movement.

In the 1840s, Delany was committed to what’s known as a strategy of “moral suasion” to bring an end to the horrific institution of slavery. He, like Douglass, believed that if blacks demonstrated virtue, intelligence, and moral seriousness to whites the latter would see the light and cooperate ending slavery. But this faith in the openness of white power to cede to black dignity took a violent hit in the 1850s with the Compromise of 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Act. The power of racism, or at least a racist aristocracy, was far more entrenched in the United States than Delany had believed.

Hence, in the 1850s, he began to argue for blacks to leave the country. As his biographer Tunde Adeleke writes, “He became convinced that America was irredeemably racist and that blacks would never secure justice. . . . Delany quickly developed an enduring reputation as a separatist.” Indeed, he became a leading promoter of African Americans returning to Africa, and he himself moved to Canada. In the 1850s, he visited Liberia, the colony founded by the American Colonization Society, to explore possibilities for a mass exodus of blacks from our racist aristocracy.

The outbreak of the Civil War, however, changed the trajectory of his career. When the war broke out, Delany sought an audience with Abraham Lincoln, hoping to persuade the president to enlist blacks in the Union cause and to make emancipation a war strategy. Lincoln eventually agreed. Delany became the first black combat major in the war and helped lead the United States Colored Troops. However, he never saw combat. The war ended not long after he was commissioned.

Instead, he became a political warrior in Reconstruction, an active member in the Republican party in South Carolina, and an advocate for what at the time often seemed to be a contradictory position: reconciliation with white southerners and full political rights for blacks.

Indeed, political rights for blacks became his great cause after the Civil War.

He was assigned to the Freedmen’s Bureau and sent to Hilton Head, South Carolina. There, he managed efforts to ensure the welfare of recently freed slaves. Delany soon found himself in the throes of Reconstruction South Carolina politics, where blacks—numerically at least—were for a short but lively period in control.

Delany’s political career in South Carolina was a series of failures. He found himself on the outs with both Radical Republicans, whom he accused of corrosive corruption, and white reactionaries, whom he tried unsuccessfully to bring around to a moderate course of gradual reform and racial reconciliation. Nevertheless, it was a vibrant period for Delany’s political thought.

His tumultuous and confusing years in South Carolina forced him to try to comprehend and clarify his own political convictions. It was here that he returned to republicanism, looking all the way back to the ancient Roman Republic. He wrote a series of pamphlets for students at Wilberforce University in which he laid out the principles of republicanism and tried to apply them to the new post-Civil War era America had entered. He explored the concept of freedom as non-domination that the Romans had donated to the world. He stressed the centrality of justice in the republican framework. And he emphasized that the republican conception of citizenship was as much about responsibilities as it was about rights.

Yet, at the same time, he also explained the ways that republicanism had always failed itself by reserving exceptional spaces for “outsiders,” be they “foreigners,” “colored people,” or “white trash.” He traced the devolution of republicanism in both ancient Rome and in the antebellum United States. In the latter, blacks were legal outsiders, living in the country but outside of the protections of law. He argued that republics tended over and over again to devolve into aristocracies, where some were made more privileged than others with respect to the portfolio of rights they enjoy.

For Delany, republicanism was not just about “No Kings!” It was about no privileged political classes at all, or “No Aristocracies!” The danger in any rights-based society, he suggested, was that those who enjoy rights will start to see their rights as a privilege to be kept from “others.”

Indeed, it is an odd but persistent phenomenon in a rights-based society. Why do I feel that my rights are threatened by others acquiring rights, too? Are rights like gold, only as valuable as they are scarce? Why couldn’t rights be like air, there for all? Why do we feel the need to hoard them?

Delany believed that the Civil War gave the United States the opportunity to convert a scarcity mentality to a platform of plentitude. It was time, at last, to shun the old race-based aristocracy in favor of a new egalitarian republic.

Here, however, he was exceptionally careful to specify exactly what he took an egalitarian republic to be. It was not, he argued, one characterized by “social equality”—that is, a society where everyone has the same level of education or the same social status. Nor was it one that hinged on “cultural equality,” as if all peoples should bleed into a common monoculture. Delany, that is, was a realist and a pluralist.

Rather, an egalitarian republic for Delany was one where each and every person enjoyed equal political rights, in addition to and over and above civil rights.

Political rights are not civil rights. What is the difference? Civil rights come down to the right to be left alone, or live and let live. Thus, a black person no less than a white person should be able to eat at a diner, go to a good school, or attend a church. We are accustomed to thinking of racial struggles in this country in terms of the advancement of such civil rights: freedom from local or national government interference in matters of association, religion, speech, education, labor, medical care, and so on. The Bill of Rights, for the most part, is a document devoted to protecting civil rights.

Delany argued that civil rights were vital, but he insisted that in the struggle for black freedom and a pluralistic but egalitarian republic, they were never enough. In order for civil rights to be effective and protected from the hoarding of others, they needed to be paired with political rights, which center on the right to exercise governing power.

Political rights, in other words, entailed the right of all citizens to take active responsibility for the political community, not just be served by it. The right of any citizen to participate in governing, be it through a vote, holding office, serving on a jury, or doing public service, he argued, was the only sure way to keep a republic from devolving again into an aristocracy. This is an often-hidden truth in our political life together: civil rights are never enough.

It is one that liberalism has not recognized frequently enough. When I say “liberalism” here, I am not talking about liberals as those people on the political Left. I am talking about the broad framework under which most politics in the United States (and many other parts of the world) have been carried out for the last century. Liberalism arose as a response to demands for greater equality among ordinary people. Like republicanism, its enemy was the aristocracy, specifically the aristocracy granted power by virtue of their name and family lineage. Before this, it was kings and aristocrats who enjoyed rights, not ordinary people. Liberalism, like republicanism, sought to extend the rights of the aristocracy to ordinary folk.

But not all rights. Rather, the focus in liberalism was on civil rights. Amid the Age of Revolutions (1776-1848), it was common to distinguish between civil and political rights, where the former (civil rights) were gradually extended to more and more people but the latter (political rights) were reserved for a special class of people (typically based on property qualifications in Europe, but in the United States frequently focused on racial designations).

The logic here went like this: the job of the government is to protect the civil rights of people. What people want from their governments is the right to be left alone: to be allowed to say what they want to say, worship how they want to worship, gather with whom they want to gather, and freely defend themselves when threatened by others. Such are “civil rights” or “civil liberties.” As long as the government was protecting these civil rights, it really did not matter who was holding political power. The right to vote, to hold political office, to serve on a jury, and other political powers were secondary, and indeed, for many liberals, seen as dangerous, for they could open up a Pandora's box of popular and “demagogic” rule.

This was the common sense among thoughtful people during the late 18th and early 19th century, from Alexander Hamilton to Alexis de Tocqueville. And so in the United States, in Europe, and in South America (where important political revolutions also happened), political rights were carefully guarded even as civil rights were expanded.

But this particular liberal project failed, over and over again. And for a reason. For as Delany recognized, the central problem in politics, contra liberals on the Right and Left, is not how to use government effectively while limiting its scope and power. Rather, the central problem in politics is how to establish and maintain the broad political power of all. If blacks were freed from slavery and left alone by the governing powers—free to work, love, and live—but they were not politically empowered, their liberty would be ever vulnerable. And indeed, this is exactly what happened in the post-Reconstruction course of American history. Delany foresaw American regression and reaction. He could read the stars because he saw the political light of political rights.

A century later, the political thinker Hannah Arendt, whom I wrote a whole book about, made the same case in a different context. Arendt, born a German Jew, was a refugee to the United States after World War II. Like Delany, she saw that what made Jews in Europe vulnerable was precisely the fact that they were kept from exercising in full the political rights of governing.

The pivotal political challenge for a country that would be fair and just, she argued, is “not how to limit power but how to establish it.” When people lack political power, they have no mechanisms by which to defend their civil rights or the civil rights of others.

So, it's Juneteenth, 2025. With the “Civil Rights” legislation of the 1950s and 1960s, a full hundred years after Delany made his case for equal political rights for blacks in America, the political rights of blacks were finally guaranteed. But even today, problems remain. Blacks make up about 14% of the U.S. population, but only 5% of American senators in 2025, and the Supreme Court is pretending that race-based political inequities in America simply don’t exist. This is because the Court tends to think about civil rights; it pays less attention to the conditions necessary for different groups of people to be politically empowered.

Why does this matter? First, people without substantive political power are just more vulnerable. In the crackdowns on Latino communities where legal citizens and legal residents are being accosted, we are now seeing just how vulnerable our neighbors are when they lack substantive political power.

Second, much of what we are calling these days “populism” is a symptom of a political culture where political power is in the red. Indeed, the political system as it is currently organized aggressively excludes everyday people from the exercise of political power beyond an occasional vote. Oligarchic money in politics, networks of disinformation and manipulation, party bosses, the lobby industry, a large segment of the population living paycheck to paycheck—such is the support structure for the 21st-century American aristocracy.

Third, when political power is scarce, people begin to hoard what they feel they have. Given the relative paucity of actual political power among ordinary American citizens, it is easy to villianize “outsiders” as the core of the problem. Indeed, this is the core pathology of the political Right today. Leaders of Right, in fact, have little interest in enhancing the political power of everyday citizens. They are instead focusing the national energies on protecting rights assumed to be scarce against the incursions of “others.”

Delany told the students of Wilberforce University,

It must be understood that no people can be free who do not themselves constitute an essential part of the ruling element of the country in which they live. Whether this element be founded on a true or false, a just or unjust basis, this status in community is necessary to personal safety. The liberty of no man is secure who controls not his own political destiny. What is true of the individual applies to a community of individuals, or society at large. To suppose otherwise, is that delusion which induces its victim, through a period of long suffering, patiently to submit to all kinds of wrong, and holds in subjection the oppressed of every country.

In other words, a people who grow used to the diminution of their political power become a people who are ever more willing to tolerate wrongs and injustices done to themselves and others.

Field Notes:

As of the writing of this post, Trump is right up on the edge of getting the United States into Israel’s war with Iran. This from a man who campaigned on, and is no doubt committed to, not getting the United States into foreign wars. Ross Douthat had a column this week (gift link) exploring the reasons why Trump may be changing his tune and readying to join Israel in a massive war in the Middle East. What Douthat fails to consider is the basic position I’ve been advocating: namely, while Trump is strong in many ways, he is and has been politically weak. His modus operandi makes him so. The only people in his “circle,” the only ones who come to him, are, in essence, courtiers—people who want to use him in some way and are not going to challenge him in any significant way. He has no authentic friends, personally or politically. And when crises arise in governance, you need friends and genuine allies to be politically strong. This is both an Aristotelian and a Machiavellian principle. My sense here is that, practically speaking, Trump is even weaker before Netanyahu than Biden was. Netanyahu is not just putting Trump off (as with Biden), he is working to pull him into a major war, knowing Trump does not want it. I hope very much that Trump has the will to resist, because while I, as much as anybody, would like to see Iran rid of nuclear weapons potential, I also am confident that the United States directly participating in this war will open a can of costly, long-term, perhaps generational, consequences. If Trump resists, it will be because of his will, not because of friends and allies joining with him to bolster his political strength. He is, politically speaking, a weak man. Netanyahu knows that. We are about to learn if strength of will of a single man is enough in matters of war and peace.

Can I just say that I had nothing to do with the rise of the “No Kings!” protests, even though before it was a thing, before people were widely talking about Trump as a would-be king, I wrote here at Civic Fields about America’s New Royalism? I love the current outrage over kings. It is an ancient and profoundly American tradition, as patriotic as apple pie. This said, I want to stress again that when I wrote about Trump as king, my stress was on a political style, a way of trying to make power work (and not work) in government. In particular, I am concerned with Trump’s love for “courtly” power—for people vying for his attention through strategies of gifts, bribes, and flattery. It is a profoundly un-American approach to political power, one that the Founders were dead-set against. I do not think this is an exclusively Trump thing, though I do think he’s particularly drawn to it and symptomatic of a bigger problem: a 21st-century American neo-aristocracy rooted in the restructuring of political power from local and state political parties to national ones that are extremely hierarchical and centralized, contrary to the way political parties best work from a democratic perspective. On this see Philip A. Wallach’s Why Congress?, a probing study of the ills of the contemporary U.S. Congress.

On a related note, I have been wondering why otherwise patriotic conservative citizens are so okay with Trump’s radical personalization of political power. There is something going on in conservative culture that has to do with a deep suspicion toward impersonal institutions, be they educational, medical, political, or ecclesial. At some point, well before liberals, conservatives started giving up on institutions (so very ironic, given traditional conservatism’s reverence for institutions). The canary in the coal mine here might have been the decline of religious denominations in favor of celebrity-led independent bible churches and megachurches. Unlike the invectives against “liberal elites”—as if conservatives were “forced out” of U.S. institutions—this phenomenon is largely internal to American conservative culture. It has something to do with American conservatism, charismatic power, and the cult of celebrity. If I were to write a book about this, I’d start (in my research at least) with Billy Graham. I’d be interested in hearing your thoughts about what first started turning conservatives away from institutions to personality-centered politics (ned@civicfields.org).