Into the Unknown!

A "public good" argument for funding useless science

This week’s Civic Fields post picks up on where we left off two weeks ago with “What is Happening to Universities?” It comes to you from M.I.T., where Katie P. Bruner teaches in the Department of Comparative Media Studies & Writing. Katie is an award-winning teacher and writer whose work focuses on the intersection of science, technology, and public life. Her writing has appeared in Rhetoric & Public Affairs, The Hedgehog Review, and The Quarterly Journal of Speech, and now Civic Fields! Katie has done a lot of thinking and writing about the role of basic science research in modern American history. I asked her to reflect on why we’d want to pour billions into seemingly useless scientific research. Enjoy! -Ned

Earlier this week, The New York Times published a report (gift link) on the dramatic drop in federal funding for science research as a result of the Trump administration’s policies. The precipitous decline in funding is getting plenty of attention at universities and regular attention at places like The New York Times, but most people are probably, at best, only barely aware of what is happening and what it means. Others may look at a bunch of the projects funded by Congress over the last decades and think good riddance!

So, since I have a perch here at MIT, Ned reached out to me and asked me to write a bit about the history of federal funding for science in the United States: a sort of who, what, why, where, and when of what became known as “basic science.”

Since World War II, the United States has spent hundreds of billions of dollars on scientific research, and among these billions, tens of billions on failed scientific research: drug trials with null results, energy research gone wrong, spacecraft gone up in flames, and new innovations never making it to market. Historically, Americans on the whole have had few complaints here. They know that scientific research and development involves risk; without a tolerance for failure, science would go nowhere.

But what about research on rat massages, or on a mathematical model for running an auction, or on why jellyfish glow in the dark? All three have been funded by American tax dollars.

In some worlds, examples like this of “useless science” vindicate the Trump administration’s slash-and-burn approach to scientific spending this year. Grants are being denied, research budgets drastically cut, award cycles cancelled, and projects stopped mid-stream. Trump’s proposed budget for 2026 would include even more cuts.

So-called “useless science” has long been known in the scientific world as “basic science.”

The National Science Foundation (NSF) defines basic science as “work undertaken primarily to acquire new knowledge of the underlying foundations of phenomena and observable facts, without any particular application or use in view.” According to the NSF, basic science accounted for nearly 25% of federal research funding during the Biden administration.

The basic argument for “basic science” goes like this: in order to know what drugs to make, or how a spaceship might tolerate interstellar travel, someone had to do more fundamental research on these physical or technical phenomena.

Spending billions of taxpayer dollars each year on research undertaken “without any particular application or use in view” may conjure in our minds a mad scientist toiling away on their pet project. Many basic science projects seem odd or of dubious relevance to anyone except the passionate researcher who may have a particular interest in a type of mold, species of beetle, or unique medical condition. Many of these projects are published in obscure journals that few read, and some are never finished or forgotten altogether.

So why do we do this? What is basic science even for?

One line of argument is that it has a direct relationship to future economic growth. Let’s call this the “Return-On-Investment” argument, or ROI.

Many defenders of basic science use ROI. Basic science, they argue, is a sound financial investment. Championing the dividends of basic science, they cite projects like ARPANET and Mosaic, which set the foundation of the internet you are reading this on, or space race-era research that led to the development of the GPS we use to find our way around, or investments in translation software that tens of millions now use when playing Duolingo. From this vantage point, cutting basic science funding is like neglecting to invest in the next Apple or Google. Economic investment in basic science, this line of thinking goes, begets economic growth. The next big idea is just around the corner.

The irony here is that ROI arguments are also at the heart of those who want to cut government funding for basic science. Trump and his appointees in the “Department of Government Efficiency” (DOGE) have been cutting away at federal investment in scientific research in the name of fiscal responsibility.

Trump is not the first politician to use ROI to cast suspicion on basic science. In the 1970s-80s, Wisconsin Senator William Proxmire publicized what he considered wasteful government spending through his monthly “Golden Fleece” award (the name referring to a con artist “fleecing” their mark). Many basic science projects were chosen for Proxmire’s public condemnation, such as an NSF project on the impact of marijuana on male sexual performance or a University of Michigan study on why humans (and some animals) clench their jaw.

DOGE and the Golden Fleece Award share an approach to basic science that presumes that for every dollar spent on research, the return should be greater. Return-On-Investment. As such, projects that require significant capital investment or projects that are of dubious return potential are de-prioritized or defunded. Science here is about economics and only economics.

So, ROI is an understandable but risky approach for defending basic science. It forces scientific research into a ledger in which it cannot thrive and may not even survive.

But there is a different historical argument in defense of basic science: the “pacemaker” argument.

Some argue that basic science benefits the nation beyond the economy. Basic science here is sometimes called “the pacemaker of technological progress.” In a road race, a pacemaker runs a consistent speed in order to signal to other runners that they need to slow down or speed up. This keeps the group of runners at a sustainable pace. An artificial pacemaker is used to create the electrical signals that tell a patient’s heart to beat at a healthy rhythm.

If we take the pacemaker metaphor seriously, then we could think of economic and market forces (such as new discoveries, consumer demand, or the latest technologies) as signals that tell the nation to speed up or slow down investment in scientific knowledge. These signals, however, may be weakened by strain or fatigue. They may be distorted by political interference, distrust, inequality, or nihilism. They may get put in the wrong hands. A tech billionaire might come along, for example, and decide to slash the federal budget.

Basic science, in this metaphor, would keep scientific research progressing at a steady pace, regardless of the health (or disease) of the economic and market forces.

The phrase “pacemaker of technological progress” comes from a 1945 report called Science The Endless Frontier. The Report was written by Vannevar Bush, a former MIT engineer who had just completed his tenure managing American research during World War II. Bush had observed how crucial basic science had been to the ability of US researchers to collaborate on urgent wartime projects such as radar, atomic weapons, and early computing. The foundation of basic science laid by researchers at American universities allowed the United States to stay strong and spring into action when World War II began.

That basic science would make U.S. researchers capable of responding quickly to national threats became a central selling point of basic science when it was marketed to the American public during the Cold War. After World War II, Bush’s Endless Frontier report led to the creation of the institutions of modern research we know today: the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and more.

The critical point here: By calling basic science a “pacemaker,” Bush was advocating for federal funding not because he thought it would necessarily be a good economic investment. His focus was on preparing America to be ready for when another war came about (a very real concern in 1945). For the next few decades, America justified basic science inasmuch as it allowed the U.S. to out-compete its enemies.

But there are limits to this argument, too. It makes science subservient not only to the nation-state but to warfare. That so much basic science funding has come through defense-related spending is no coincidence.

There is a third and, to my mind, more satisfactory argument to be made for basic science. Here, we might use a bit of speculative fiction. This line of thinking asks us to imagine what would have happened if we had not invested in basic science.

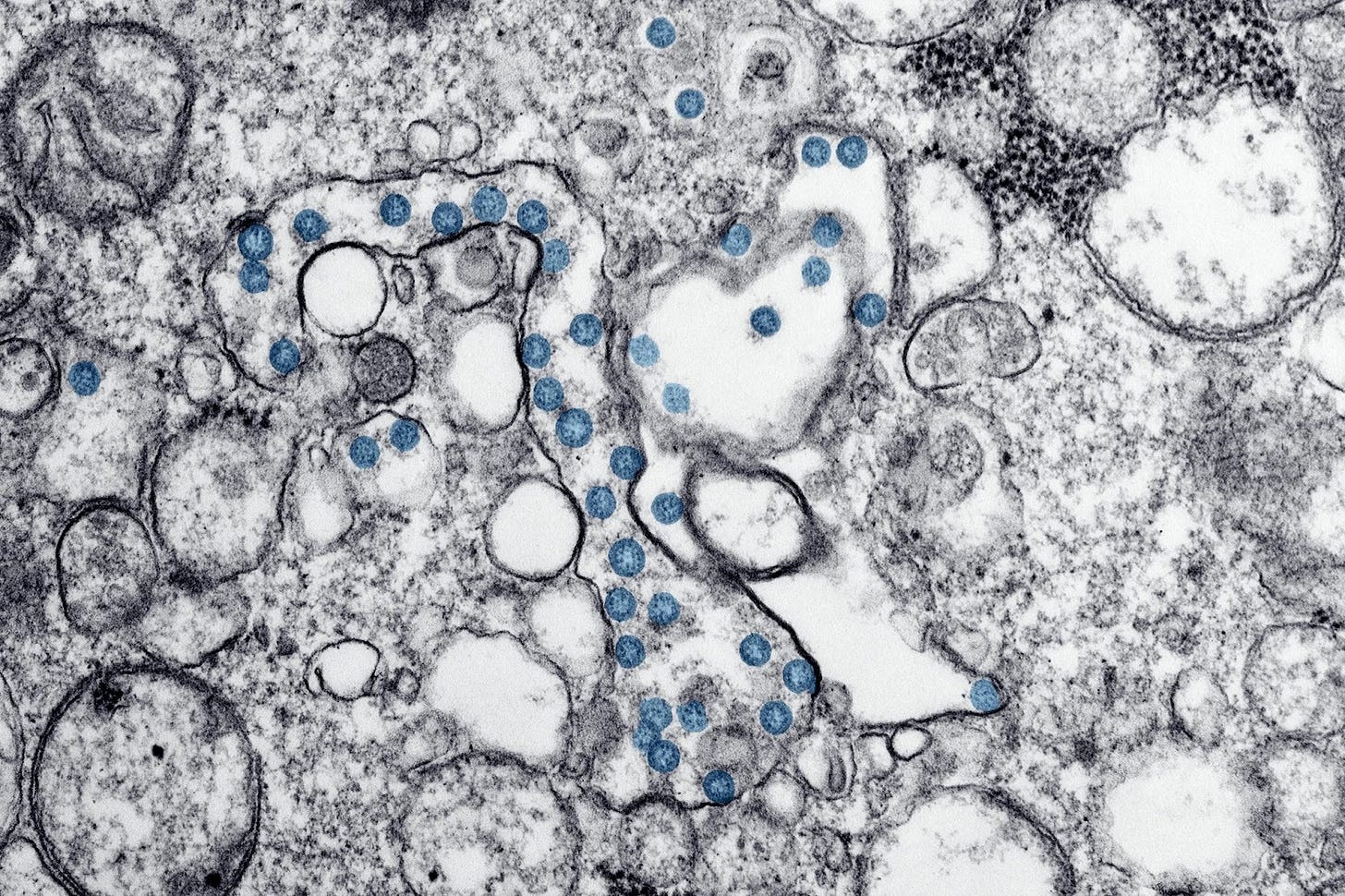

Inspired by Senator Proxmire’s “Golden Fleece Award,” the Golden Goose Award recognizes three publicly funded projects each year that have “resulted in significant societal impact.” One of their recipients in 2021 was Dr. Katalin Karikó and Dr. Drew Weissman for their work on the Pfizer/Moderna vaccine developed during the COVID-19 pandemic. This vaccine was the first real-world application of the basic science research on mRNA that Dr. Karikó and Dr. Weissman had been conducting since the 1980s.

The race to develop the COVID-19 vaccine was a sprint, and the American research community was healthy enough to participate because they had a pacemaker implanted decades prior. Market forces would not have cut it.

Without basic science, we could be living in a world in which the pandemic was still around.

Here, hindsight helps us appreciate how basic science can contribute to the public good. But support for the basic science being done today (or late last year, before it was cut) depends not on hindsight, nor even on foresight (for the benefits of basic science are radically unpredictable), but on a kind of “no-sight.” Basic science is not quite the same as flying blind, but it is flying into unknown territory.

This, to me, is the best justification for basic science. We should invest in it precisely because we don’t know. What would it look like if more researchers did not have to promise that their work would have any particular outcome? What if we did not pretend to know what the future will bring? What if we invest in knowledge not because we know it will stimulate the economy, or because it will lead to the next “big idea,” or because it will strengthen American diplomacy, but because it is inherently good to learn more or, conversely, to learn more about how little we in fact know?

Of course, there’s nothing inherently wrong with conducting research with a goal in mind, and there’s wisdom in preparing for future threats. But a culture in which we regularly invest in activities meant to evoke a collective sense of humility, wonder, and the unknown might just be a counterbalance against the confident ignorance that seems to plague our current political moment.

Because let’s be honest, we don’t know what is coming. We can try to make complex models of the future, we can do our best to anticipate and plan, and we can try to maximize ROI. But we cannot escape the path of the unknown. Science undertaken without a “practical use in view” is perhaps the most clear-eyed way to proceed into the unknown.