Perfect Days

A meditation on service workers, politics, and “red republicanism”

I have spent the last few weeks exploring an “-ism,” republicanism. I know that “-isms” are dangerous for a writer. Since they seem like airy abstractions, they risk groundlessness. “Prefer the specific to the general,” one venerable manual of style recommends, “the definite to the vague, the concrete to the abstract.” Strunk and White continue,

If those who have studied the art of writing are in accord on any one point, it is this: the surest way to arouse and hold the reader’s attention is by being specific, definite, and concrete. The greatest writers—Homer, Dante, Shakespeare—are effective largely because they deal in particulars and report the details that matter.

I have zero pretensions of being a Homer, Dante, or Shakespeare, but I do want to deal in details that matter. Am I betraying this by spending time here on “-isms”?

But “-isms” are also dangerous because they so often function as ghostly fantasms in our online and televised political discourse. Take “socialism,” a word that connotes for some a world catastrophe, for others a universal utopia, and yet for others simple nonsense. But can anybody tell us what “socialism” actually means in the particulars? So much of our political discourse strikes me as quixotic. We joust with verbal “-isms” as though they are real knights.

Still, I can’t give up on “-isms.” We can’t, not if we want to think about life outside of our front door. Any time any group of any significant size comes together, they must rely on some abstractions in order to make sense of what they are doing. Where “-isms” go wrong is when they are used to enforce doctrinaire systems. Where they go right is when they are used as guideposts. At their best, “-isms” are comprehensive suggestions that organize and direct a community's attitudes, ideas, and attention in positive and productive ways.

So, I am going to stick with republicanism. But this week at least, I am also going to heed the Homeric spirit and start with a story. Then I’ll call upon the Socratic spirit to pose a question about the story.

The story is of a man named Hirayama, as told in Wim Wenders’ 2023 film Perfect Days. The question I want to explore is, What ‘-ism’ out there could both make sense of, and properly honor, the life of Hirayama?

Those of you who have seen it know that Perfect Days (currently streaming on Hulu and Amazon) is not a typical film. It does not really have a plot. It has only one main character, Hirayama (played spectacularly by Kōji Yakusho). It takes place in modern-day Tokyo, and what little dialogue there is is in Japanese (with subtitles). And yet every review I’ve encountered of Perfect Days raves about it. I recommend it if you have not seen it. It may end up being a film you watch more than once.

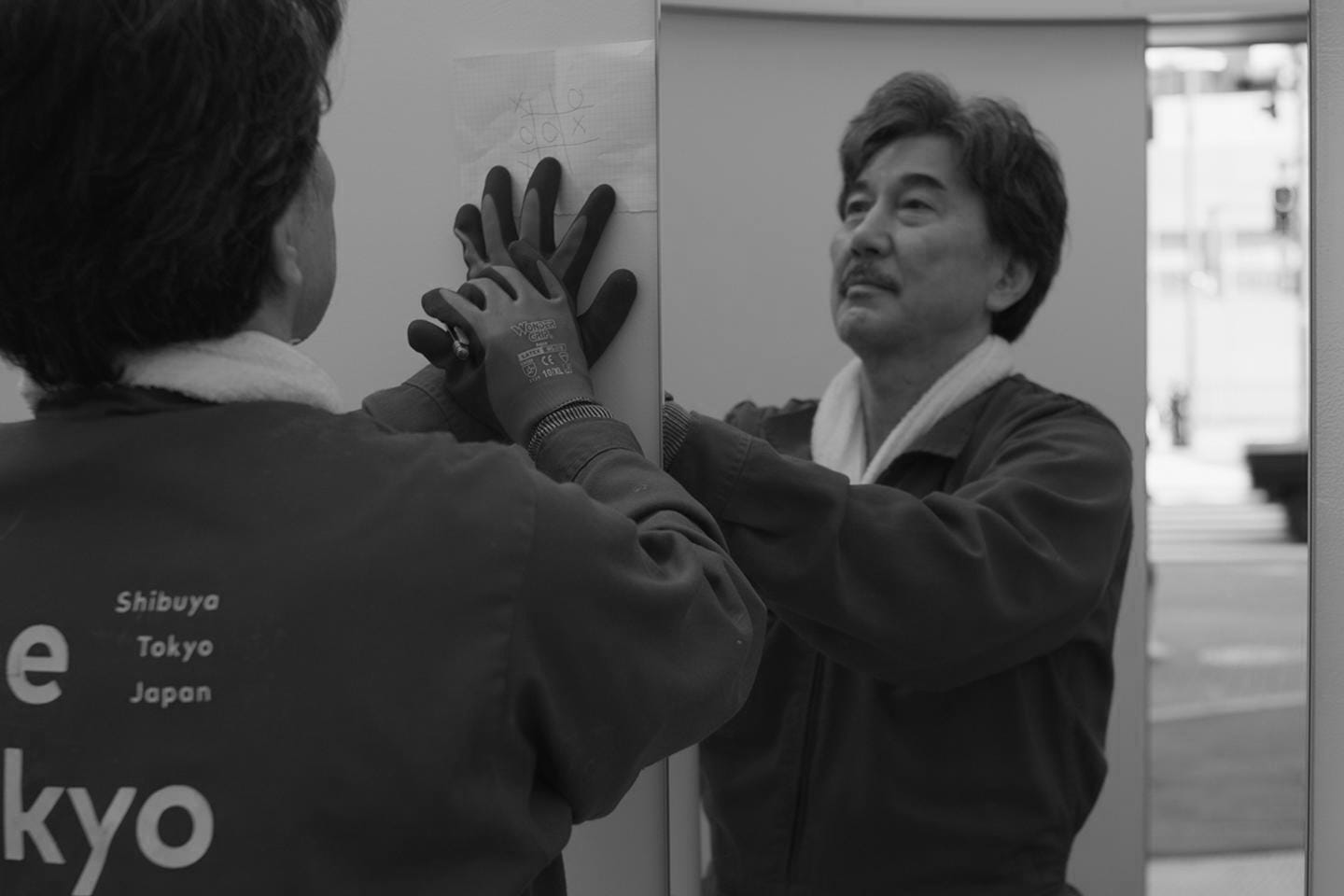

Hirayama is a professional toilet cleaner. Monday through Friday, he goes from one public bathroom to another, subjecting them to scrutinous cleanings. The film is nothing more than a chronicle of the routines of Hirayama’s life. It presents almost as a documentary.

Hirayama lives alone in a sparse but clean and well-maintained apartment in the working district of Oshiage, on the eastern side of Tokyo. We meet him at the beginning of the film, asleep on the floor, greeting him as he awakes. He rolls up his bed, brushes his teeth, waters his treasured collection of tree saplings, and walks out of his apartment for work, looking up to the sky each morning with a smile and joyful breath. He grabs a canned coffee from a nearby vending machine, enters his work van, pops in a cassette tape from his large collection of 60s and 70s rock and R&B music, and drives through Tokyo to arrive at his first assignment for the day.

His work is meticulous. He even cleans under the toilets, using a hand-held mirror. Each midday, he goes to the same public park for lunch, where he ritualistically takes a picture of the trees overhead with a small film camera.

Then more toilet cleaning, before heading home again, changing clothes, heading to the local bath house for a shower, and then riding his bicycle to a local diner for dinner. Returning home, he makes his bed and lies down with a book (he reads Faulkner) until growing sleepy and turning off the light.

Perfect Days follows Hirayama through several such days and into the weekend, where we see him laundering his clothes, riding his bicycle through the streets of Tokyo, praying at a temple, and enjoying a nice dinner at a restaurant he frequents each weekend.

To be sure, there are interruptions to his routine—an estranged niece visits him, a coworker begs him for money, his van gets a flat tire, and he ends up out late one night drinking with a new friend—but these interruptions do not disrupt his life. Hirayama is a man who takes things as they come. He is a man who knows both contentment and joy.

Perfect Days is a work of art. It has been widely celebrated as one of the best films in recent years. Much more could be said about it. But I think I’ve done justice to the basic outline of Hirayama’s life as it is portrayed in the film.

Now, the question: What ‘-ism’ out there could both make sense of, and properly honor, the life of Hirayama?

I want to be clear here that I do not think all lives need to be comprehended by an “-ism,” be it a cultural or political “-ism.” But I have reasons for thinking that Wim Wenders, the filmmaker, wants us to ask this question about Hirayama.

In a 2024 interview in The New York Times, Wenders relates how he was inspired to make the film as he watched the civic spirit erode in his home city of Berlin during the pandemic. If you know Wenders’ wider work, you know that political questions are never far from the screen, though they often appear obliquely.

Indeed, the globe-wide civic devastation caused by the pandemic is the quiet backdrop to Perfect Days. The public bathrooms that Hirayama so carefully cleans are actual architectural and hygienic gems built in Tokyo for the 2020 Olympics. Leaders of Tokyo had commissioned a number of world-renowned architects to build them. It is remarkable to think of bathrooms as great public works, built out of public pride. But what could be more in the spirit of civic health than providing beautiful, clean, and sophisticated sites for one of our most basic needs?

“I have never seen any toilet anywhere in the world that was done with so much care for detail,” Wenders told The New York Times.

But it was not the bathrooms themselves that grabbed Wenders' attention as much as the sanitary workers who served the city by cleaning them. Perfect Days is a tribute to these workers. It honors them by trying to comprehend the form of life, or the kind of person, that would take such pride in the cleaning of public toilets. But more indirectly, the film asks questions about the kind of society that would honor such work as a worthy contribution to the civic spirit.

So, let’s turn to some “-isms.”

If “liberalism” were personified, perhaps as a character introduced into Perfect Days, what would he say of Hirayama’s life? He would say, I suggest, that Hirayama is doing what he has to do to make a living. He might celebrate Hirayama for finding joy in it. He might compliment him for his great life hacks (as this podcast cringingly does).

Liberalism would also likely say that he wished it were not so that people had to clean public toilets. He would admit it is degrading. He might talk about a not-too-distant future when robots could do the dirty work and people like Hirayama could find more dignified jobs. And he would marvel that Hirayama is obviously educated, sophisticated in literature (again, he reads Faulkner) and music (Nina Simone, thank you). But liberalism would also wonder at how Hirayama could have ended up in such a low station.

If “socialism” were personified in the film, she might stress the plight of menial workers like Hirayama, who clearly hangs on the bottom of the vocational ladder. She would point out the fancy cars that pass him by as he does his work, or talk about how the glitter of Tokyo reflects directly off the backs of toilet cleaners.

Or she may instead celebrate the life of Hirayama as a socialist’s dream. He clearly has a living wage. He enjoys the leisure of good food and good books. He seems to have no anxieties about medical insurance or retirement. His joy, which is manifest throughout the film, is a testament to what life could be in an economically just society.

Note here, however, that neither liberalism nor socialism has anything to say about the public service that Hirayama does each day. None honors him as a worthy public servant. They are limited to apprehending his life, if they apprehend it at all, in economic terms—to them all, his is an instance of the form of life belonging to homo economicus. There is for them little to no sense of the dignity of the res publica, the “public thing,” that Hirayama so dutifully and carefully serves.

But his life is not just an economic life; it is a public life.

Therefore, what would “republicanism” have to say?

Republicanism would certainly see Hirayama, if they saw him at all, as an exemplar of the civic spirit, just as Wenders wished. But, as much as it pains me to say it, republicanism would have a hard time seeing Hirayama.

As a service worker, he would likely fall beneath the horizon of “public servants” that republicanism historically esteems. Republicanism holds up office holders, citizen soldiers, or other examples of great public service and sacrifice. Republicanism esteems people who win badges, medals of honor, and are honored in memorial holidays. Toilet cleaners do not count.

It’s for this reason that I consider Perfect Days to be pushing us to think about what could be. It asks, “What if?” We might think of it as a semi-utopian film.

The New York Times reported that “some viewers have found the character [Hirayama] to represent an unrealistic fantasy.” So he is. The film, after all, is called “Perfect Days.” It is not a realistic account of the life of a public toilet cleaner in contemporary capitalist society. But neither is the story of Hirayama unrealistic—that is, incapable of being real. It seems so only to those who lack an imagination for something different.

The service sector is now the largest employment sector in the world, comprising half the world’s jobs. For all the ways the Trump administration is pushing to bring manufacturing back stateside, the fact is that it is the service sector that has dominated the American economy both nationally and globally for some time now, and will continue to. The dream of widespread factory jobs is long dead, no matter how hard Trump & Co. claim they want to bring them back. We live increasingly in a service-economy world.

Therefore, if there is any hope of effectively revivifying the civic spirit, we will have to not only include service workers but, in some sense, center them. We need a politics that can not only bring them security, but dignity. It will need to not only provide a living wage, sufficient and affordable medical care and retirement security, education, and decent work conditions, it will need to be able to recognize and honor the ordinary, mundane, and often invisible forms of public service that people do outside of a strictly economic frame of appreciation.

I take Perfect Days to be, at least in part, a meditation on what such a politics might look like.

None of our “-isms,” at least as they are now, are up to the task of integrating the service sector with the civic spirit. Perhaps we need a new, as yet unheard of “-ism,” or perhaps we can rehabilitate an older one. (I realize, of course, that most service jobs are not concerned with cleaning public toilets, but it’s a place to start thinking about broader issues.)

I, frankly, see no path forward here for liberalism (understood broadly, as encompassing both liberals and conservatives). It is entrenched in an economic framework that can’t give sufficient room to the civic spirit.

I am also skeptical that socialism, even democratic socialism, can break free from the prism of homo economicus to see ordinary folk in their patriotic, communal, and civic dimensions. While I agree with some of the basic economic policy positions of, say, Bernie Sanders, I do not see him thinking much beyond people in their economic aspects.

I want to, therefore, propose, as a mere invitation to think with me, something like “red republicanism.”

In Canada and the United Kingdom, there has been, off and on, a push for “Red Toryism.” In outlook and sentiment, Red Tories share a good deal with those today who in the United States call themselves “national conservatives.” As I understand it, the basic argument coming from Red Tories and national conservatives is that the economy should be regulated by the state to serve the needs of the “nation,” where the “nation” is understood as a relatively homogeneous culture with clear “in group” and “out group” dynamics. These folks are “red” not because they are communists—they are not—but because they advocate left-leaning economic policies, even as they are culturally and politically conservative.

But Red Toryism and national conservatism are, in fact, unrealistic projects. Their insistence on cultural homogeneity defies both national and global realities. It is therefore not surprising that certain proponents of Red Toryism and national conservatism harbor downright noxious and racist ideologies. When reality bites, “-isms” typically find a scapegoat.

I am imagining, by contrast, “red republicanism” as a synthesis of left-leaning economic policies with a robust civic spirit suitable for an inescapably pluralistic society. It, too, would rely on “in group” and “out group” dynamics, but in a way that is about drawing people into the civic “in group,” regardless of race, creed, gender, or ethnicity and leaving in the “out group” those interests that look no further than their own selfish gain.

Red republicanism would be an “-ism” that could uphold public toilets as points of civic pride, and public toilet cleaners as citizens worthy of a secure living and the esteem that is due all public servants. It would be an “-ism” that could both comprehend and honor a man like Hirayama.

Field Notes:

One friend of the newsletter took my post on Neo-Royalism to mean that I was suggesting that Trump was literally seeking to become king of the United States. I am sorry if I was not clear enough, but I was writing of a “mode of operation” or “political style” rather than an actual official designation. Thus, my focus on the “court” and courtly politics. Part of what’s so interesting about Kathleen Bartoloni-Tuazon’s book, For Fear of an Elected King, which covers early debates in Congress about how to refer to the executive, is that even after the U.S. Constitution was ratified, many Americans, including many elected representatives, feared that the Constitution still left room for the reign of an “elected king.” As Bartoloni-Tuazon chronicles, George Washington himself was quite conscious of this possibility and tried to set precedents to keep it from happening. But the way he worked against the arrival of a new American monarch was largely by inculcating a distinct “republican” political style, in contradistinction to the court-centered royalism of Europe in his day. My colleague and mentor, Robert Hariman, has a wonderful chapter on the “republican style” in his book Political Style: The Artistry of Power.

Speaking of the (royal) court, Trump’s sons have started a members-only dinner club in D.C. Dues? $500,000 annually. Meanwhile, Vietnam responded to Trump’s 45% tariff by pursing multi-billion dollar private deals with the Trump Organization and giving Musk’s Starlink rights to internet service. When old-fashioned republicans cried out against royalty and monarchy back in the day, one of their chief cries was “corruption!” Never in American history have we seen anything like the staggering corruption of the Trump administration. And it goes hand-in-hand with court politics.

The “happiness” study is back. Finland tops the charts again, with the other Scandinavian countries right behind. This article (gift link), however, suggests that the key to Scandinavian happiness may not be Hygge after all, but the art of setting low expectations. I am not sure I am okay with low expectations. I might rather suffer some unhappiness. As for the study itself, two findings stand out. I quote: “First, people are much too pessimistic about the benevolence of others. For example, when wallets were dropped in the street by researchers, the proportion of returned wallets was far higher than people expected. This is hugely encouraging. Second, our wellbeing depends on our perceptions of others’ benevolence, as well as their actual benevolence. Since we underestimate the kindness of others, our wellbeing can be improved by receiving information about their true benevolence.”

What does the United States look like right now from abroad? From Africa? This op-ed, “Understanding America’s economic decline through a wider lens,” in the Nigerian newspaper The Guardian, offers an interesting window, not the least for the ways its author writes without any hem-hawing about the realities of race in our current national crises.