Repent or Die!

A crash course on Robert Putnam’s vision for civic renewal

Dear Readers,

First of all, I want to thank you for reading Civic Fields. It has grown quickly, more so than I expected. I especially want to thank those of you who have encouraged me with nice words over the last several weeks. I don’t take it for granted. My goal is for Civic Fields to continue to grow. I’d like to experiment with the format here and there. I’d like to bring other writers in. I am thinking about a podcast. The core concept, however, will remain firm: Engaging and thoughtful commentary about our current civic state and its repair. You can expect something in this vein most Thursday mornings this year.

One goal I have is to offer a series of “crash courses” focused on different people thinking in one way or another about prospects for civic renewal. These will not be mere wikipedia entries. They will be interpretive, engaged pieces on key civic thinkers. The post below on Robert Putnam begins that series.

I have an email account set up just for Civic Fields: ned@civicfields.org. Feel free to email me with comments, questions, or interesting tidbits. And please consider sharing Civic Fields with others.

Last night I watched Kevin Durant cry. Durant is the greatest men’s Olympic basketball player ever, a two-time NBA champion, a two-time Final’s MVP, and a guaranteed NBA Hall of Famer. A child of poverty from Prince George's County, Maryland, his rather remarkable mother—a single teenage mom when Kevin was born—fought tooth and nail to see her children escape destitution. Durant’s path took him to the University of Texas, where he became the first freshman ever to win the National College Player of the Year award. He entered the draft in 2007, signing with the Seattle Supersonics, and ran away with the NBA’s Rookie of the Year. This year, his seventeenth in the NBA, he is earning $51,000,000 for the season.

But last night I watched him cry. During an interview in the new Netflix documentary on the 2024 summer Olympic basketball tournament, his voice starts to shake, and tears well up in his eyes:

Durant: “Coming together, basketball, man, it’s just like, it’s incredible to see that. . . . So as much as I can, like, bring us together that way, that’s what I try to do.” [Long pause]

Interviewer: “I can tell how much that means to you.”

Durant: “Nah, for sure, because it’s like I come from a neighborhood where people don’t even talk to each other. So much hate in the world too, it’s like, when you finally . . . when people start laughing and joking before the game of ball, it’s cool to me, so like it gets me emotional, dawg.”

“Coming together . . . man . . . it’s just incredible to see that.” Indeed, we are living in a time when such an utterly ordinary thing can make a grown man cry. “People start laughing and joking.” Reason for a multi-millionaire who’s been through it to choke up.

In 1995, the political scientist Robert Putnam published an article in the Journal of Democracy called “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital.” Five years later, he published a book by the same name. Few works of scholarship have gotten more attention in the United States over the last quarter century. Presidents, People Magazine, and innumerable podcasts have fretted over how Americans are “bowling alone.”

Putnam’s basic thesis is simple. According to his research, a wide range of indicators show a dramatic decline in participation in clubs, unions, professional societies, and volunteer organizations in the United States since the 1970s. People started bowling alone rather than in groups or clubs. The decline in “joining,” he argued, brought about an equivalent drop in what Putnam called “social capital.”

By analogy with notions of physical capital and human capital—tools and training that enhance individual productivity—“social capital” refers to features of social organization such as networks, norms, and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit. (“Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital,” Journal of Democracy 6.1 [January 1, 1995], p. 67)

In plain English, a decline in social capital means the weakening of social ties. This, Putnam argues, brings about a breakdown in social trust, cooperation, civic engagement, healthy politics, and effective government.

Putnam also suggests the loss of social capital affects mental and physical health. People are more likely to die sooner than they otherwise would. Other studies have suggested something similar. A 2013 study showed that even just a little bit of social interaction with strangers—for example, making small talk with the clerk at the grocery store—was correlated with higher levels of personal happiness. A 2021 study showed similar effects among people who talked to strangers on the train. A 2014 study went so far as to argue that people with low social interactions are more likely to suffer from heart attacks than those who scored high on social cohesion. The years of COVID produced some studies showing that people with high amounts of social capital were less likely to get severely sick from the virus than those with low levels. Social capital functioned like a vaccine.

In 2023, a documentary about Putnam’s work came out. It’s called, appropriately, Join or Die. It’s worth a watch.

Robert Putnam is now in his 80s. Nevertheless, the last few years have been quite good to him. He’s been busy doing interviews on radio shows and podcasts, arguing that an American revival needs to start with a reinvestment in social capital. As if to put an exclamation point on the theme of “Join or Die,” in 2020 he published what he considers his magnum opus, The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again.

The Upswing goes beyond anything Putnam had done before. Rather than limiting himself to sociological studies spanning a few decades, The Upswing covers over a century’s worth of data on American civic life. And rather than focusing just on social capital, he looks at four additional variables:

the strength of social capital;

the extent of economic inequality;

the preponderance of political compromise; and

the altruistic fabric of cultural values.

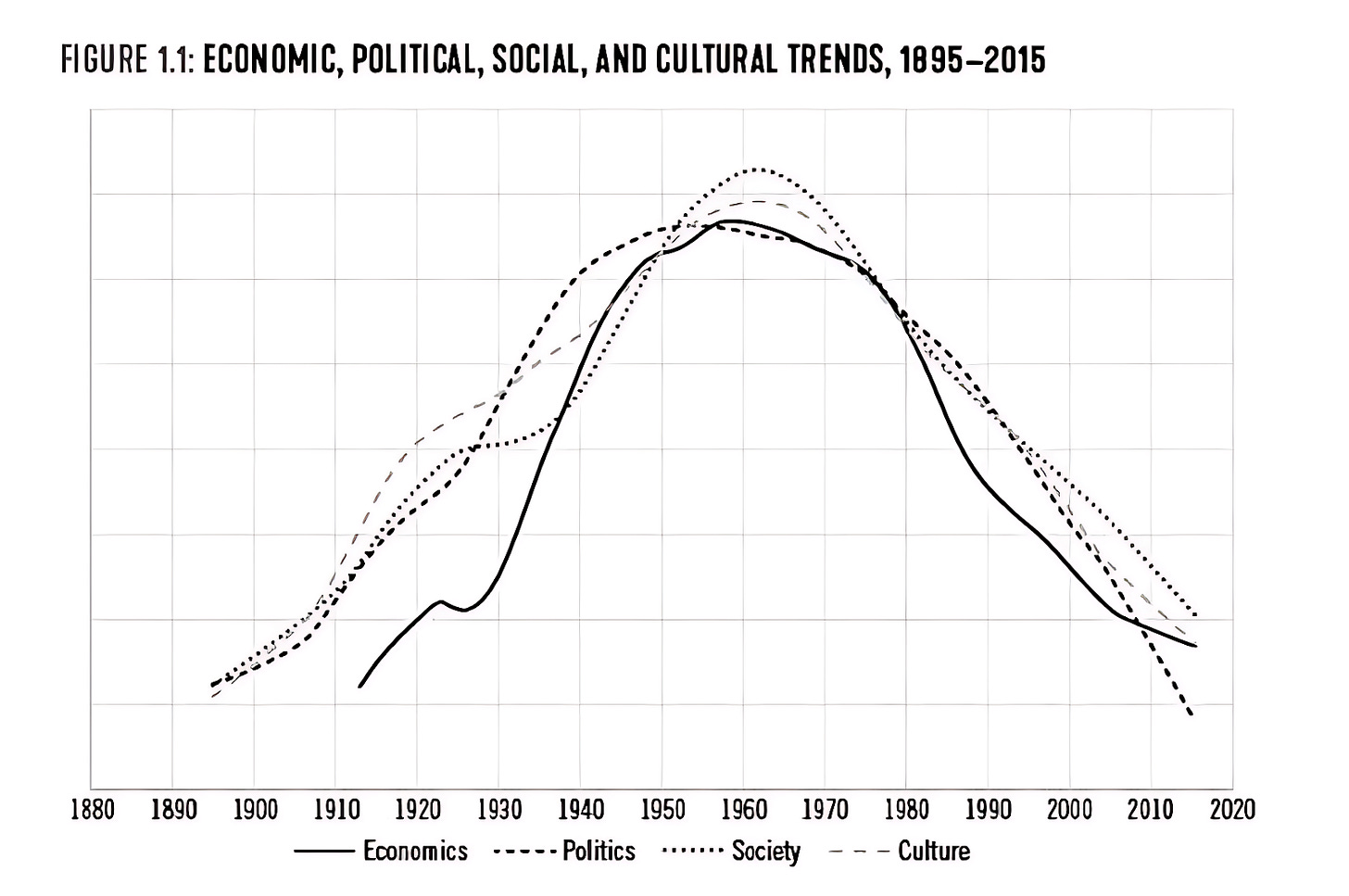

The book’s long-view assessment of American civic life looks like an upside-down U. Drawing on reams of historical data, Putnam argues that after the dire years of the 1880s and 1890s, in the early 1900s the United States began to see a long, gradual “upswing” in all four variables: social capital, economic equality, political compromise, and altruistic cultural values. These variables more or less moved upward together until the 1960s, when they topped out. A sharp downturn began in the 1970s, and we have continued to spiral down: declining social capital, greater economic inequality, less political compromise, and egoistic cultural values.

In his typical colloquial style, Putnam describes the society seen in the upswing as a “We” society but the society after the 1960s as an “I” society.

The film Join or Die argues that the key to reversing this downward trend is, well, joining. Get involved. Stop sitting alone in front of your screen. Find a book club, a bridge club, a volunteer organization, a cause to join with others. Or, to echo Kevin Durant, go to a basketball game and laugh and joke with others. Celebrate things that are communal and civic. Hooray for parades!

This is how Putnam is destined to be read. He’s put himself on the map as the American prophet for “joining.”

However, there has been another Putnamesque message lurking beneath the surface of his studies. It’s what I, only somewhat facetiously, would term Repent or Die! Putnam is a very good social scientist, but he’s also a strong moralist (in the best sense of the word). He has a moral message to tell, and he claims he has the data to prove it.

In The Upswing, as well as in various interviews he has done, Putnam argues that when trying to pinpoint what exactly was responsible for the upswing in American civic life that began in the early 1900s, he was surprised to find that the leading indicator was what he calls a “moral awakening.” One would expect, he states, that economic indicators would be front stage: the less economic inequality and destitution, the more social cohesion. But Putnam argues (as the chart above from the book shows) that economic amelioration follows moral reawakening. The problem with America today is that we are morally deficient. This, in fact, is his core message.

Putnam has expressed his “surprise” at this finding as if the data had to prove it to him before he would believe it. Yet, it has been a theme in his work over the years.

In 1993 he published a study of contemporary Italian politics called Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. The book looked at the effects that certain major political reforms in Italy in the 1970s had over a two-decade period. It contrasted the relative success of the reforms in northern Italy to the relative failure of identical reforms in the southern part of the country. This was Putnam’s first major foray into “social capital.” Chapter 6, called “Social Capital and Institutional Success,” argues that the reasons for the successes in northern Italy were rooted in the greater quantity of social capital in the region. There was, to put it plainly, a greater sense of participation and belonging in the north relative to the south. This is the well-known Putnamian thesis and anticipates the arguments he made in Bowling Alone about American society.

But it is chapter 9 of Making Democracy Work that is most interesting. It’s called “Tracing the Roots of the Civic Community.” I’d venture to say it is the least read of the ten chapters of the book, for it consists of a long and sometimes quite dense review of Italian political history dating back to the late Middle Ages. Yet, it is here that Putnam offers what he describes as the “decisive” explanation for why northern Italy was doing better than southern Italy in the late 20th century. Putnam traces the advent of what he calls “communal republicanism” in northern Italy back to the 12th century. Way back then Italians in the north developed a civic ethic that came to permeate their society for centuries.

Putnam quotes from a 13th-century guild statute to show what this ethic entailed. The law promises, “Fraternal assistance in necessity of whatever kind,” “hospitality towards strangers, when passing through the town,” and “obligation of offering comfort in the case of debility” among other social commitments. These medieval Italians, in other words, pledged to take care of each other. Civic responsibility was a moral commitment.

Later, as Putnam chronicles, northern Italy was overrun by a new generation of feudal lords. Nevertheless, he argues, a culture of mutual aid and civic responsibility persisted beneath the battles and squabbles of the overlords. The tradition of moral civic commitments was more powerful than the schemes of the well-armed oligarchs, keeping the soil of northern Italy fertile for generations for more egalitarian political reforms.

Civic renewal, Putnam is saying, may be expressed in social capital, but it is rooted in basic moral commitments to togetherness, even with the stranger. Social capital, like economic fairness, is downstream from such moral commitments—or so Putnam argues.

Economic thinkers will resist Putnam’s centering of moral reform in social cohesion. Sociologists like James Davidson Hunter believe that the United States simply may not have the moral fabric in place to survive its culture wars. And social darwinists will continue to hold out faith in markets or biology to make things right, at least for some people.

I am all for thinking about practical economic reforms and I hope to take up Hunter’s sober arguments in the future. But I read Putnam as calling us to take a moral leap toward civic life regardless of what others might say. There is indeed a faith in his work that such acts will bear fruit, if not in our lifetime, then in those of generations to come. I also appreciate that in Putnam’s view, this moral leap does not need to be dour, and indeed should not be dour. It includes laughing, joking, and a good ballgame. These can be acts of civic faith.

The last thing I can do is speak for Kevin Durant. Nevertheless, watching him tear up I saw hints of Putnam’s vision. Durant was, in essence, crying over the work of social capital. And in his manifest desire for togetherness—this is a man who knows what it is to live in a community where people don’t even talk to each other—is itself the seed of a kind of radical moral commitment. Those tears came from someplace deep. He felt it. So do I.