Three Cheers for the Democratic Party!

It’s starting to look like a political party, and that’s a good thing

When I started writing Civic Fields I had three main purposes in mind.

First, was an effort to reconnect with political and moral roots that might improve our lot. Second, was to highlight the ways in which civic health depends not only on what goes on in Washington, D.C., but what happens at the level of the local community. Third, I wanted Civic Fields to continue the work I’ve done in the classroom and in print, defending politics against its critics.

This last item is the umbrella that covers the first two and is at the heart of my diagnosis of our current cultural and civic ills. When people grow disgusted with politics, they either “check out” or “lock in”—the former produces apathy, the latter authoritarianism. Our first alienation as a country is an alienation from politics.

Politics is about how difference and disagreement needs to be buckled up with compromise and community. Most of what we think of as “politics” today is a far cry from its authentic expression. It is the stuff of media cycles, propaganda artists, pollsters, and bullies, not citizens, neighbors, negotiators, and persuaders.

Given this, I’ve been heartened recently by what we seem to be witnessing in the Democratic Party: An opening toward politics?

I have said in these pages before that I am not a member of the Democratic Party. It, like the Republican Party, has become far too top-down and centralized. That is, by my logic, political parties have become less political—and that is a bad thing, for it means it has become too closed, exclusionary, and ideological. Thankfully, what the Democratic Party has not done is become a cult of personality—à la the Republican Party. That would be a worst-case scenario, not just for the Democratic Party, but for the country. The cult of personality, as we are seeing on the Right, is too easily grows oppressive, anti-democratic, corrupting, and cruel. But while the Democratic Party has this crucial difference with its Republican counterpart, it has been too top-down and ideologically monolithic.

That may be starting to change.

Three things have happened in the last two weeks that give me some reason to believe that the Democratic Party is starting to become an actual political party again. When I say “political,” I mean a party that is capable of holding together different constituencies with quite different perspectives. Because we in the United States are stuck in a two-party system—and that will not change—it is crucial that our political parties be “big tent” parties. Otherwise, they become vehicles for making enemies, alienating the “other,” and enforcing ideology. I don’t identify as a Democrat today because it says too much to do so. And all the more so if you are a Republican. Membership in a political party, by contrast, should say only a little bit about you.

My reasons for some optimism? The first thing that happened was the elections last week, which Democrats won in a rout. As many have noted, the types of candidates and the types of issues featured in the state and local elections at issue were quite diverse. There was no ideological uniformity across the board. Each candidate tailored their message to their specific context and electorate.

This is how politics is supposed to work, and how it goes to work. It should not be about ideological conformity or loyalty to the man. It should be about the matching of values and policies to particular contexts, with the goal of actually doing something for the electorate, not simply winning their vote and securing party power.

Which brings me to the second thing that has heartened me recently. What I just said here is more or less what Ezra Klein has been repeating recently (see here and here, both gift links). On a national level, Klein, the New York Times columnist, is the most important voice in the Democratic Party. He can move mountains. For example, on a policy level, he is partly responsible for the recent changes the state of California made with respect to housing regulations—weakening regulations so as to allow for the more rapid construction of desperately needed housing in the state, and this in a state infamous for resistance to such change.

Klein has recently taken to arguing that the Democratic Party needs to become a “big tent” party capable of holding together a bunch of different constituencies representing a bunch of different perspectives, even ones that are blatantly at odds with one another. He’s embraced “politics” in the way Civic Fields has framed it all along: ideological litmus tests need to come to an end, differences need to be acknowledged and even encouraged, and being a “Democrat” needs to mean less, not more.

This means Democrats need to focus on only a few big national issues—affordability, opposition to authoritarian cruelty, and—I wish Klein would add—law enforcement that is both professional and civilian (in contrast to the militarized security that has been a trump card for the Right). Meanwhile, different Democrats in different parts of the country can and should represent their constituencies differently from each other. This, after all, is what representation is all about. It is not rocket science, though, given the direction of both parties over the last decades, it certainly can seem that way.

So, I’m glad to be hearing all this from a strategy and policy mouthpiece of the Democratic Party.

The third reason I am heartened is the fact that seven Democratic senators (plus an independent who caucuses with the Democrats) broke with their party this week to support a Republican bill to end the shutdown. Ironically, Klein has been critical of this move. It seems he is still struggling to learn his own lessons. I think, by contrast, that it is a promising sign for two reasons.

First, it is consistent with the principle of representation. Senators should not be agents of parties, though they absolutely need to work with their parties, but rather representatives of their constituencies. A lot of folks are being hurt by the shutdown, some in more areas than others. At some point, practical issues have to take precedence over party loyalty. We would live in a different and better country if more politicians thought this way.

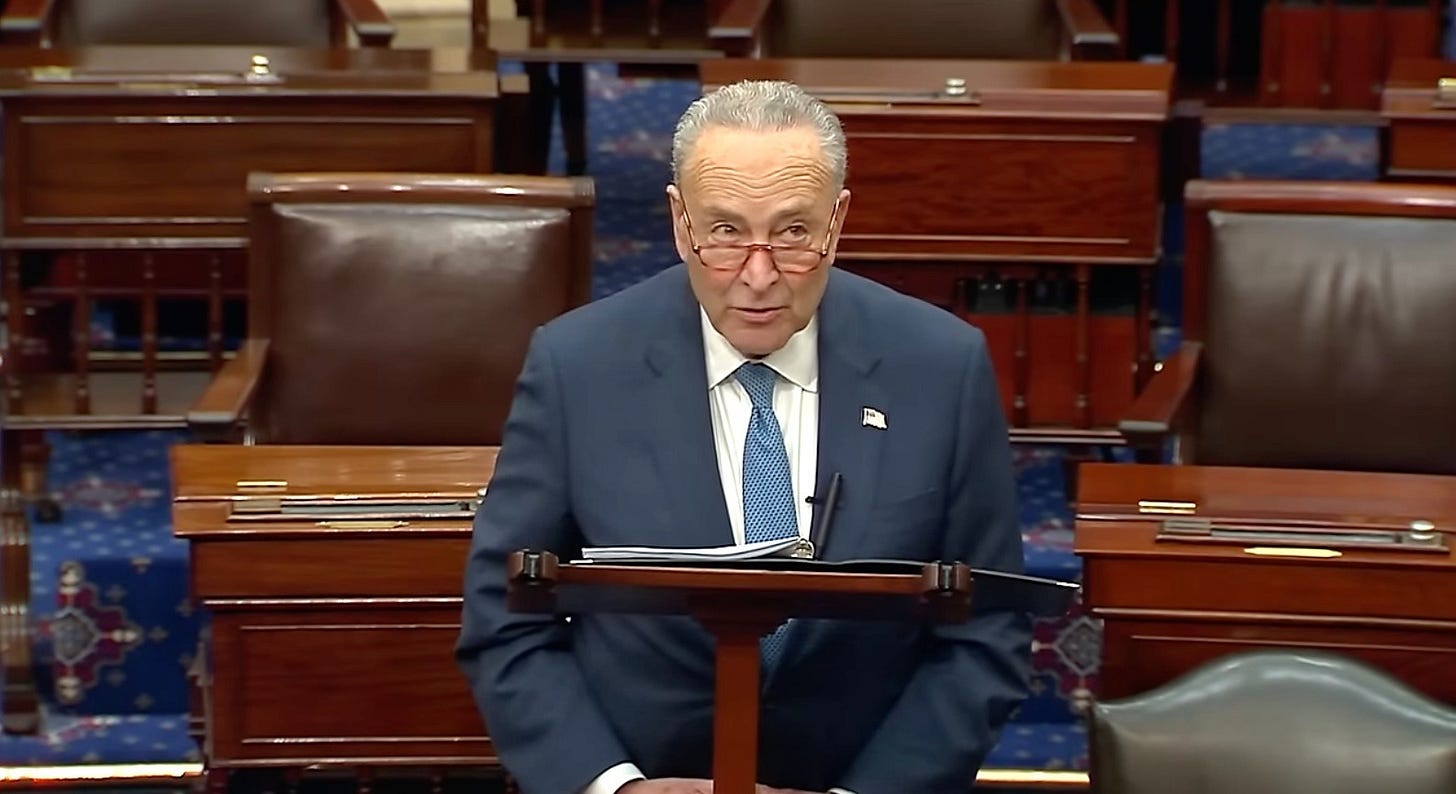

Second, it speaks to the growing weakness of Chuck Schumer, and that is a very good thing—not only because Schumer has proved himself to be a very unlikable politician but because a central problem in governance right now is the top-down structure of our political parties. They need to be democratized, not disciplined.

Together with Mamdani’s victory in Schumer’s home city of New York, the Democratic Party is trending away from top-down control. Given the widespread hatred for Trump and the very legitimate worries about the new form of American authoritarianism, it is understandable that the opposition party would want to walk in lock step. But that’s the wrong move.

Digging in, contra Bernie, is not the best way forward for the Democratic Party or for combating oligarchy. For democratization in the country must start with democratization in our political parties. That some Democrats decided they could not toe the line indefinitely, no matter what the party leadership said, is a good thing. It means that maybe, just maybe, more political space may be opening up in at least one party.