Civility in an Age of Incivility

Can the damage be undone?

Last week Bruce Springsteen made some news for using the opening of his new “Land of Hope and Dreams” tour to comment at length before a U.K. audience on the Trump administration.

“In my home, the America I love, the America I have written about, that has been a beacon of hope and liberty for 250 years, is currently in the hands of a corrupt, incompetent, and treasonous administration,” he began. “Tonight, we ask all who believe in democracy and the best of our American spirit to rise with us, raise your voices against authoritarianism and let freedom ring.”

Rock n’ roll stars chastising those in power is almost as old as rock n’ roll itself. I grew up listening to bands like the Clash, Midnight Oil, and Bob Marley. Bruce Springsteen’s been writing political songs for ages, not the least “Born in the USA.”

So, as rock stars go, his comments sounded more like a speech on the floor of the House of Representatives than one before a rowdy crowd of fans.

“The last check on power, after the checks and balances of government have failed, are the people — you and me. It’s in the union of people around a common set of values. Now that’s all that stands between democracy and authoritarianism. So at the end of the day, all we’ve really got is each other,” he continued.

He even sat down on stage for a bit to talk through his views.

“In America, the richest men are taking satisfaction in abandoning the world’s poorest children to sickness and death. This is happening now.”

“In my country, they are taking sadistic pleasure in the pain that they inflict on loyal American workers, they’re rolling back historic civil rights legislation that led to a more just and plural society,” he said.

“They’re abandoning our great allies and siding with dictators against those struggling for their freedom. They’re defunding American universities that won’t bow down to their ideological demands. They’re removing residents off American streets, and without due process of law, are deporting them to foreign detention centers and prisons. This is all happening now.”

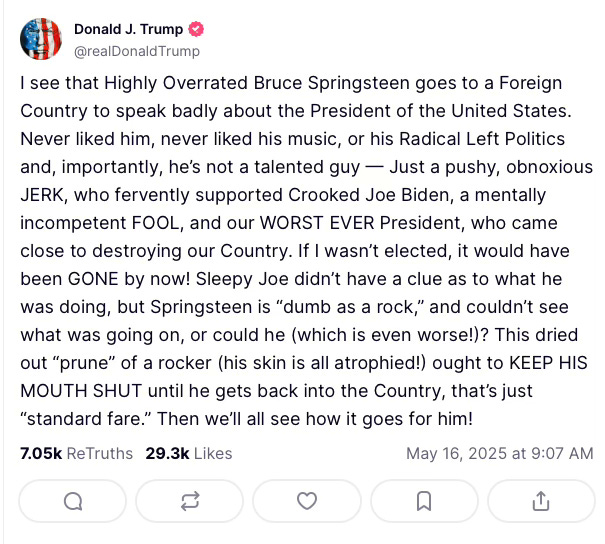

These comments are civil. They are not “nice” or “gentle” or “tolerant,” but are civil. For a contrast, witness Trump’s response on Truth Social:

I know such verbal blows, insults, and threats are par on the Trump course. I know of all the thousands of social media posts he has made, this one’s relatively tame. But knowing all of this, I just can’t bring myself to wink at it, shrugging my shoulders with a “same ol’, same ol’” sigh. This is the President of the United States, after all.

And yet a shrug of the shoulders is now the overwhelming response of American citizens.

For all the corrupting influence of Trump, it may be his outright rejection of civility that imperils the nation the most. Unlike written laws or concrete policies, civility is at the very heart of the social contract. It centers on a tacit agreement to play by rules that have broad support and consensus behind them. It is the core of the norms-based politics essential to functioning democracy.

Do I sound moralistic? If so, that is the surest sign of the corrosive effect of Trump on the country. It is not, in fact, too much to ask a president to communicate like a president. Rather, it should be the baseline. Does condemning Trump’s gross and cruel speech make me a prude? No. It just makes me civil.

This little newsletter is called “Civic Fields,” so it might be good to write about what is being invoked with the “civic.” What is “the civic”? Why does it matter? Who’s it for? Why am I spending so much time thinking about it? And why are you reading about it?

As we approach the summer (during which I am going to dial down the frequency of Civic Fields to focus on writing a book) I want to reflect on the “civil” and the “civic” in an age of incivility.

I admit, civility is very hard to define. If we get too narrow in our ideas about civility we miss its point. For civility has just one essential characteristic: civility is about speaking and behaving in such a way that communicates a commitment to stay within bounds of respect. What exactly those bounds are can be contested, and they can change. But to speak or act in a civil manner is to implicitly communicate to an audience, “I want to keep our political struggles within bounds of respect that you can recognize.”

This view of civility, I know, is thin. But I am wary of thick or overly prescriptive views of civility because they can be used to control public discourse rather and enable and facilitate it. You can say very harsh things in public that are nevertheless respectful: to the facts, to the reality of the situation, to what is politically at stake. Truth is a form of respect.

So civility is not necessarily about being nice. It can be, but need not be. The main thing with civility is to communicate the intent to stay within those bounds of respect.

Because it is thin, civility is inherently precious and fragile. Unlike, say, a country’s natural resources, civility has no bedrock in which to lodge itself until it is needed. It is more like bubbles we blow into the public wind: civility floats in the air for all to see, or to pop.

Moreover, unlike, say, capitalism, civility no longer has robust institutional means of securing itself. As the sociologist John Hall writes in The Importance of Being Civil, civility has no “secure structural base” anymore to safeguard its operations. There was a time just a few decades ago when media were organized around a few dominant national news agencies, each competing for the cultural and political mean in order to secure profits. This structural arrangement forced public discourse toward the middle, keeping it well within respectable bounds. Cable deregulation, followed by the Internet and the advent of social media, blew up this structure. Now profits are made across the media monopoly board by driving discourse to extremes.

Therefore, Hall argues that it is all the more critical that elites model civility. Civility has become entirely an ethical commitment, whereas it used to also be buttressed by economic incentives.

Indeed, years before Trump rode down the golden escalator in 2015, elites competing for attention and money began to cede the stage to incivility. In the 1990s, congress joined talk radio as a stage for outrage. Soon after, social media companies concluded that civility does not sell all that well. Prominent media personalities on Cable TV began lapping up a MMA rhetorical style clipped into soundbites and reposted on social media.

Incivility has come from above. It has moved from elite culture downward. It is structurally incentivized. They have done this to us.

As a consequence, to walk into the civic sphere today is little different than walking into an unkept and smelly public restroom. The civic sphere, like said restroom, is something we need, and need badly, but it has been actively trashed by elite vandals. We have to hold our noses as we do our business.

Therefore, negative emotions rule the day in civic life.

Most people simply just don’t want to be part of politics and civic life, given how out-of-bounds it is at the highest level.

It is hard to be non-partisan when one party, the GOP, has as its leader a person utterly devoted to incivility. Like an alcoholic father, Trump forces you to take sides. You are either with him or against him, an enemy or an enabler. And he does this by being habitually uncivil.

In an age of incivility, the main problem is not that people don’t know “how” to be constructive and civil in debate as much as they don’t know if it is okay to be so, or, even worse, if it will make any difference.

Most distressing, voting patterns and social-media metrics suggest that at least a plurality of people in the United States just don’t think civility matters all that much to the functioning of the country.

This is a grave error. For civility is about boundaries and limits, a sine qua non of politics. To say civility does not matter all that much is to say boundaries and limits do not matter all that much; and that is the definition of tyranny, be it the tyranny of a few persons or that of a captured plurality of the population.

To be clear, I do not consider incivility to be Trump’s worst crime. That belongs to his callous and sudden cutting of USAID funds, which served 120 million people globally and made up nearly 50% of the world’s humanitarian aid. Children are in graves today that would be otherwise still be living. Millions could die in the future. Cutting off USAID was not a mere policy shift or reprioritization. It was a murderous attack on the powerless poor of the world done in the name of scoring retributive points.

It was, that is, the “policy” equivalent of one of Trump’s Truth Social posts.

The connection between Trump’s approach to Truth Social and his approach to governing is real and strong. If Trump cared about civility, he would have also cared about the consequences of his governing actions. Civility is not just a “style.” It reaches into the substance of a person’s character.

Can civility be saved in an age of mass incivility? Not easily. I am not even sure that I think it is likely.

However, I am not without reason for thinking it can at least make a bit of a comeback. Part of the reason that I think it is critical that we turn our attention more deliberately to the “civic” is because norms of civility can be protected on more local levels. Indeed, civility today depends for its sustenance entirely on forms of everyday communicative cooperation that says “We agree to keep our very real political struggles within bounds.” As long as people are doing this on a local level, it is possible they might start demanding it again on a national level.

I also have some hope here because I have an unwavering faith in reality. Part of the problem with incivility is that it does not work, at least if by “work” we mean persuade, convince, or entice people who are not already part of the bandwagon. Incivility turns such people off. I know, of course, that there are plenty of folks in our public world who have no interest in bringing others in and are quite content to preach to the choir. There’s money to be made there. But that only leaves the door open for those who are willing to try to persuade others to see things differently. Here, civility is a good start.

Field Notes:

In part to keep fresh for Civic Fields and in part because I am endlessly curious, I listen to a lot of podcasts. The best thing I’ve heard over the last couple of months came out this week on, of all places, The New York Times’ “Modern Love” series. It is an interview with the family therapist Terry Real (gift link) and it is about the plight of men in today’s world. In the interview, Terry Real rather brilliantly gets at some of the challenges men face in a culture that, among other things, prizes bravado and burning things up over civility and building things up. I am not going to be able to do justice to the pathos or the wisdom of the interview here. I encourage you to listen for yourself. But I can outline the basic dilemma Real explores in his work. He observes that, in general, men today are taught to exhibit “grandiosity” but hide shame. (With women, he says, it is often the opposite.) Grandiosity can take all sorts of forms, but among many younger men today, particularly if they are tuned in to the manosphere, it takes on a noxious, combative, and domineering form. Real says of therapists, “We have done a great job of helping people for 50 years come up from shame. But we’ve been ridiculously ineffective at helping people come down from grandiosity.” Coming down from grandiosity, he argues, means growing up. He states, “A boy’s question of the world is: What have you got for me? It’s gratification. . . . A man’s question of the world is: What do you need?” We are in desperate need of a world where men are asking others what they need rather than “what’s in it for me?”

In light of the very disturbing reporting about just how bad off Biden was mentally and physically late in his term, I have been thinking quite a bit about the paradox of the simultaneous strength and weakness of America’s political parties. On the one hand, the two parties are exceptionally strong in two important ways: (1) we are near all-time highs in popular partisanship (for the portion of the country for whom party still matters, it matters a great deal); and (2) top-down control of each of the political parties is at all-time highs. (Congress, for example, has become an extension of the two political parties, as controlled by a few leaders, rather than a deliberative body in its own right.) Yet, on the other hand, both political parties are so weak as to be helpless before leaders who betray them, as Biden and his administration did in hiding his ailments and as Trump does almost weekly by breaking from historic party priorities and presidential norms. I think this paradox is another indication of just how much we misunderstand the real character of political power. We think it is about top-down control, when in fact it is about deliberative distribution. As political parties have become more organized around top-down leaders, they have grown less powerful when it comes to addressing crises. I know it sounds weird, but control is not power. The senior leadership of the Democratic Party was for a while able to control the narrative about Biden’s mental state, but they were helpless to do anything about it until Biden himself historically flopped on the national debate stage. The GOP is desperately working to control the narrative about Trump’s erratic tariffs, but they are equally unable to do anything about it. If party power was more distributed and deliberative, in Madisonian fashion, we would not find ourselves beset as a country with presidents who are unfit for the office, as we have been now for much of the last decade.