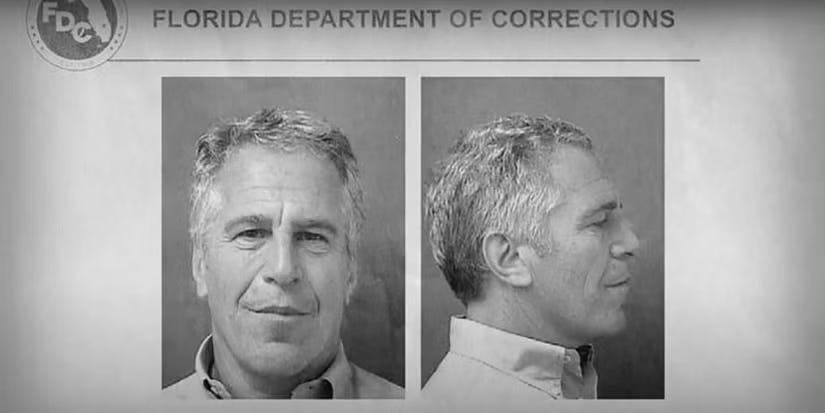

What the Epstein Files Reveal about Trumpism

For me, a moment of lucidity in an age of distraction

I know that I said that I’d be limiting Civic Fields missives this summer and that it was just last week that you heard from me, but all the news about the Epstein Files has offered me a moment of lucidity about Trumpism that I thought I better hammer out before it escapes me.

I have a good friend who is an investigator. Some of his work has involved domestic abuse cases. He’s told me that one of the things you learn about domestic abuse is that the thing you really think is going to break the system of abuse—a revelation, getting caught in a big lie, an intervention from a friend or family member—rarely does. Rather, it is typically something you never quite anticipated that breaks the spell.

I have thought about this insight a lot over the last couple of weeks as the Epstein story has been unfolding. There are so many things in the Trump years that I thought for sure would break the system—Trump getting caught on Access Hollywood bragging about sexual assault; COVID; two impeachments; January 6—and yet all for naught. The man bragged he could shoot someone in broad daylight on 5th Avenue and his supporters would still support him. Maybe he was right?

The Epstein Files may end up being yet another great escape for the president, I don’t know. But things do feel different here than they did with those other major events, even though those events were more consequential for the nation the “real world.” The Trump coalition seems to be cracking over Epstein in ways it has not before. The president seems to be feeling the heat in ways that he’s never before. Whereas with January 6 he waddled off to the White House to watch the rebellion on television, he’s now scolding his supporters for their interest in a scandal that he himself has deliberately helped make bigger than life.

What is going on here? As I have been thinking about this, I have started to feel that even if Epstein does not break Trumpism, it will, better than anything else to date, expose its political and cultural logic. There’s something to learn here, if not fully understand.

Fifteen years ago a Spanish sociologist named Manuel Castells published a trilogy called The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture. Volume 1 was called The Rise of the Network Society, and in it Castells takes a long look at, among other things, the history of media and technology in Western society and their effects on culture and society. Near the end of his chapter on communication technologies, he introduces the concept of real virtuality. This is the concept I have been thinking about recently.

What does Castells mean by “real virtuality”? He is very careful to first say what he does not mean. He does not mean that somehow in the 21st century we have become so saturated with media and symbols that we’ve lost touch with reality. As long as humans have enjoyed some form of language, reality, he observes, has always been communicated through symbols: “All realities are communicated through symbols.” The “virtual” and “real,” therefore, have always been intermixed.

Nevertheless, he argues that “real virtuality” is a new thing. What’s different about it, he argues, is the intensity of the symbolic. Here’s what Castells writes:

It is a system in which reality itself (that is, people’s material/symbolic existence) is entirely captured, fully immersed in a virtual image setting, in the world of make believe, in which appearances are not just on the screen through which experience is communicated, but they become the experience.

To put the idea in slightly more straightforward terms, Castells is saying that “real virtuality” is a condition where experience becomes limited to and identical with the “symbolic.” The symbolic goes all the way down. An entire world of experience is wrapped up in a symbolic world.

Note that this is not the same thing as talking about total immersion in a virtual world, as though we were living in the Matrix or the Truman Show. Part of what is different about “real virtuality,” at least as I understand it, is that it is limited. Nevertheless, within its limited realm it is total—all the way down. It is more like going into a movie theater and being totally immersed in the film, and then exiting into the other symbolic world in which we live, the “real world.”

This, I think, is what is so basic to Trumpism. (Here I am going beyond Trump himself to talk about the political and cultural phenomenon, global in extent, that he represents.) A huge part of Trumpism is a way of doing politics, even a way of “being political,” that is intensely and entirely limited to “a virtual image setting.” While you are in it, it’s all screen. It’s all virtual.

Again, don’t get me (or Castells) wrong: the Epstein case is real, with real victims and real perpetrators, but the Epstein obsession—which has gone so far in the last week as to shut down Congress—is all virtual. Political experience has become identical here with “a virtual image setting” (and it turns out that “real virtuality” is much more difficult for any one person, including a very powerful person like Trump, to control).

Trumpism, the Epstein case helps us see, is less about the dominance of Trump the man and more about the dominance of “a virtual image setting” that is conducive to Trump’s hold on power—at least until now. It may be Trumpism, however, that brings down Trump, at least in terms of his base.

But just like the immersive movie theater experience, this is but half of Trumpism. The other half, as I argued last week, is more traditional politics: policy, laws, court rulings, executive orders, etc. And, as I argued last week, Trumpism is here just another iteration of Dick-Cheney-style Republicanism. It’s the other symbolic world we have to live in, one where “enemies” are ubiquitous, crony capitalism thrives, the poor are always at risk, and the rich always need more tax breaks.

One might say that politics has always been caught between two worlds, at least in modern times. Leaders construct appearances for the public, but then do the nitty-gritty work of governing more behind the scenes. The reputation of politicians as inherent hypocrites is derived from this dynamic. The goal of critical citizenship, then, becomes separating the signal from the noise, reality from appearances.

But this is exactly where I think Trumpism is different. Critical citizenship—that is being a thoughtful, observant citizen—before Trumpism is not about distinguishing signal from noise, reality from appearance, but rather about the capacity to navigate, simultaneously, two very different powerful and real symbolic environments—let’s call them “real reality” and “real virtuality”—at the same time, and without confusing the two, and in such a way that one recognizes that they are equally important, equally meaningful, equally significant for our political life.

At first, all the outrage over the Epstein Files felt to me like just another giant distraction. But as I have followed this story, Trumpism has become more lucid to me: the Epstein Files matter because “real virtuality” is a real part of our current political life together and an integral part of the structure of Trumpism. The trumped-up hype and outrage and scandal is a full half of our real political world.

So, if the Trump coalition cracks over a conspiracy . . . well, who would have thunk it?