History Needs Hitches

Roughing up history along the Freedom Trail

In the name of “fostering unity,” the Trump administration recently ordered national parks and other government sites of commemoration to remove objects or exhibits that “inappropriately disparage Americans past or living.” What’s “inappropriate,” one wonders? Trump himself has suggested anything that throws a hitch in a smooth narrative of American history—for example, discussing “how bad Slavery was.”

Last week, I set out with Civic Fields on a walk along Boston’s Freedom Trail. We considered crooks and heroes, as well as crooks who are treated like heroes and heroes that had some crookedness to them. The history of this land is full of hitches. Nothing is simply black or white. So be it: just as the evening light can be more luminous than the bright shine of midday, grey can help us see more clearly than black or white.

Part of the reason I think it is valuable to walk the Freedom Trail, literally or virtually, is to reflect on the hitches in American history. The trail does not offer a smooth history. It’s roughed up. Especially in an era like our own, when culture wars have become history wars, confronting complications, contradictions, silences, inadequacies, and partialities as we approach history can have real civic benefits.

Boston is a city of hitches. As we saw last week, it is a city of neighborhoods, divided not only by history and geography, but often by language and race. You’ll hear Korean and Chinese in Chinatown, Irish accents in Southie, people speaking Italian in the North End, and Spanish in East Boston and Jamaica Plain. Recently, there have been new waves of immigrants from the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Brazil, and Mexico. There is a sense that Boston is our city and ready again to rebel against ICE authoritarianism if the need arises. But at the very same time, people talk about the need for immigrants to “integrate” into American culture. Boston loves its immigrants, but wants immigrants to be less immigrant-like.

Boston is not just a city of immigrants, it’s full of transplants from other parts of the country. There are so many colleges, universities, hospitals, and start-ups that there are plenty of people from other places. Not one member of my university department, for example, is from Boston, but we are all a part of the city now. Belonging means something more complex than being from here. The city has a super-strong identity without being provincial.

Beyond Boston, Massachusetts is an odd mix politically. The patriotism of the state is conspicuous. American flags fly in front of or on top of historic buildings and line residential streets. But the flag here does not mean “Republican” or “Trump” as it does in much of the rest of the country. It stands askance and at a symbolic distance from the ideological orbit of Fox News and military parades. I appreciate that. Conservatism here, similarly, can take on a complex New England flavor. Mitt Romney was governor, but under his purview the state started a single-payer healthcare program that became the model for Obamacare.

On our walk along the Freedom Trail last week, I left us at the North End, that old working-class Italian neighborhood that today is a thriving multi-ethnic community. This week, we’ll pick back up at the Old State House, situated in downtown (what today we Bostonians unfortunately have taken to calling the “Financial District”). And standing here in front of the Old State House, we find hitches.

The Old State House was originally the governor’s quarters when Massachusetts was a British colony. As an ever-present reminder of this history, on top of the building are two statues, one a lion and the other a unicorn encircled by a chain. The lion represents England, and the unicorn Scotland. In the 18th century, England and Scotland were the epicenters of British imperial activity—Scotland sent a disproportionate number of men out to serve as imperial administrators—and Boston was an important imperial outpost.

The statues of the lion and the unicorn stood as trophies of sorts to the British Empire. When the American Revolution ended, they were ripped from their perch. Abigail Adams talks in her diary about how they were destroyed in a giant bonfire in victory celebration at the end of the Revolutionary War. But in a fever of historical restoration that took place in the late 1800s, a period in which the United States was reconciling itself to its old British foe, replicas of the lion and unicorn were placed back on top of the Old State House. Go figure.

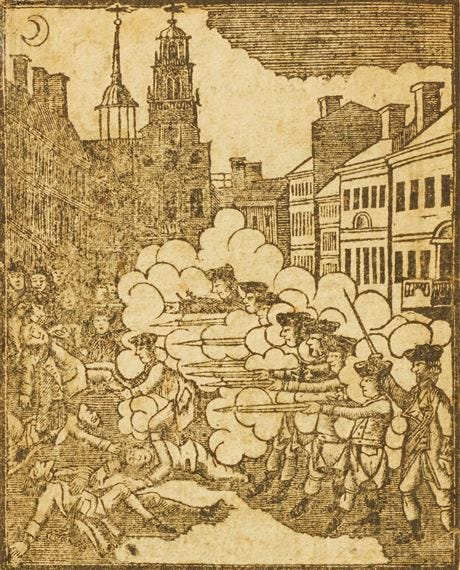

Right in front of the Old State House is where the Boston Massacre took place in 1770. Here British soldiers opened fire on a crowd of colonists, killing five and wounding several others. The massacre helped to stoke anti-monarchial sentiment. Ironically, the great American hero John Adams served as the defense lawyer for the soldiers who did the killing. He argued it was all a big misunderstanding: someone shouted “fire,” but it was likely a shout about a nearby building that had caught fire. Adams was a good lawyer. The soldiers were acquitted.

Sam Adams (distantly related to John), Paul Revere, and other Sons of Liberty made woodcuts and posters about the Boston Massacre, decrying the evils of British authoritarianism. They debated whether or not to portray in them Crispus Attucks, a black man who had escaped enslavement and who was killed in the massacre. They chose not to, although Attucks was buried along with the other colonists killed that day in the Granary Burying Ground. Today, you can find a tombstone marking his grave.

It was from the office balcony of the Old State House that the Declaration of Independence was first read to a crowd of colonists as the revolutionaries sought to drum up support for their fledgling rebellion. Reading it from the colonial governor’s manse must have felt like a giant middle finger. Every July 4th, it is read again.

From the Old State House, we can go to Faneuil Hall (pronounced Fan-yule, like Daniel), less than a quarter mile away. This place has been called the “cradle of democracy.” Peter Fanuile was a businessman and wealthy trader, in part from the slave trade, who built the building in order for voting citizens (white, male, landowners) to come together and deliberate on issues of common concern. It was used as an assembly hall until 1822, although it still holds important civic and symbolic weight. Obama and Mitt Romney have both spoken there. AIDS activists protested there.

Another historic gathering space is not that far away from Faneuil Hall, Boston Common. The Common (not commons) was originally a common in the British sense: it was where people brought their livestock to graze. The city of Boston bought the land in 1634 from a hermit who had been living there. Before that, it was the land of the Massachusett people.

The Common has long been a space for public gathering. British soldiers were camped there during the occupation of Boston in the Revolutionary War. Public executions by hanging took place there. Marches and other gatherings of citizens took place. Now Pride is held here, and protests, and free Shakespeare performances. You can ice skate here in the winter, or walk through the paths designed by Frederick Law Olmsted (who also designed Central Park in NYC). The Boston Public Gardens nearby are also a highlight. At the foot of the new State House is the terminus of the Freedom Trail, and you can look back at the Common.

As I walk along the Freedom Trail and stand before these historic sites, I keep thinking about how all histories that are worth telling have a burr in them, convolutions in keeping with the complexity of the human condition. Why, really, do we want histories that are smooth and pristine? Are we that unsure of ourselves?

Today the White House professes it is worried about a “distorted narrative driven by ideology rather than truth.”

Some truths: British soldiers killed colonists and were exonerated in part through the efforts of a Founding Father. Boston colonists bought the land of the Common, but none of the signs there today mention how these men—and they were all men—came to own the land that would have been originally inhabited by indigenous peoples who had their own rights to it. Founding heroes conveniently left out the heroic sacrifice of a black man.

But these truths barely approach the level of critique. Pointing them out is a gesture that doesn’t even rise to the level of a systemic critique of settler colonialism or racism. But in these insane and inane days, I guess anything that does not repeat the smooth, shimmering polish of American history can seem like a grand challenge to the ideology of national greatness.