The Egalitarian Declaration

An Independence Day reflection from Civic Fields

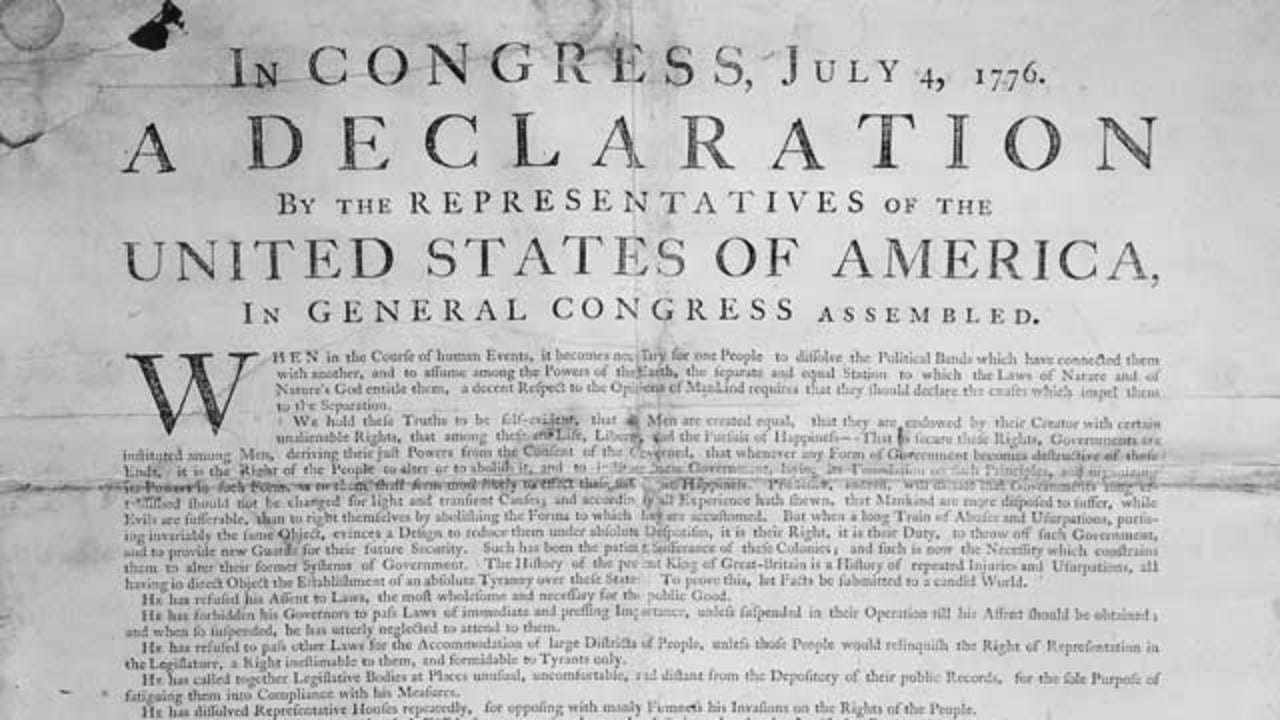

Today, July 4, Independence Day, Americans celebrate the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, that long list of grievances—to which is appended a stupendous preamble—that announced to the British and the world that the thirteen colonies were no longer willing to be part of the Empire. Curiously, Americans celebrate this day, July 4, not because it was the day that the colonies formally divorced the Crown—that happened on July 2, 1776—but because it was on July 4 that the “United States of America” declared it so. The revolutionaries, that is, thought words mattered. The deed was not done until it was declared to the world.

Nevertheless, for all the ways in which July 4 is America’s biggest national holiday, the Declaration itself has long held an uneven and sometimes rocky relationship to American politics. It is often cited, but not much read. Its fame, really, comes down to a single sentence found in its preamble:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

From these words, whole political philosophies have been constructed, and arguably whole political worlds. This grand universal claim, derived from a complex mixture of theology, philosophy, and English and Dutch political history, has profoundly informed political debates and developments in the United States and the world.

But this famous sentence was just the premise in an elaborate argument for the right of the governed to “alter or abolish” a destructive government and institute a new one. That is to say, the famous “We hold these truths to be self-evident” statement was written as a rational for political revolution, not for political policy.

Americans, therefore, have throughout their history struggled with what to do with these words. From the get-go it was self-evident to the founders that by working from such a radically egalitarian premise they were opening themselves up to accusations of hypocrisy, particularly with respect to slavery. Indeed, Jefferson wanted to include in the document a statement accusing King George of forcing the slave trade upon the Americas. (Jefferson would later blame South Carolina and Georgia for forcing its the removal of this clause, even as he makes clear in his autobiography that the debates about whether to include or remove the clause were not about the dignity of blacks but about diplomacy with England.) In the immediate historical context of the Declaration, it is clear that the “We hold these truths to be self-evident” statement was meant to provide justification for a particular and isolated political act, not to offer a grand and universal philosophical statement about human equality.

This was more than tragic. It was wrong. The founders were indeed unabashed hypocrites. A number of them knew this, including Jefferson. Others, as legal scholars Joseph Fishkin and William Forbath have written in their book The Anti-Oligarchy Constitution, tried to square the circle by propagating racist theories of black inferiority:

On its face, slavery clashed with the Declaration’s “self-evident” truths. How exactly could American slavery comport with the nation’s founding commitments? How could one square slavery with a form of government that promised to secure for all the governed the “inalienable rights” to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness? From 1776 onward, there were always voices raising these questions. The only answer that the slaveholder could give them, the only defense that seemed to allow American slavery to coexist with American democracy, was a racial one: Black racial inferiority justified slavery, and justified applying the principles of the Declaration only to whites.

Nevertheless, even with all of this horrid history in view, the Declaration is still well worth celebrating for it was and for what it would become. Without it, American slavery would not have been so easily open to accusations of hypocrisy, immorality, and wickedness in antebellum America. As early as 1777, anti-slavery activists relied on it to make their case. And without it, American reformers in the 19th century would not have had a key American text to cite over and over in opposing various forms of injustice, slavery above all. Historical texts are like marriage vows: they take on new meanings as time unfolds. We can condemn the founders as hypocrites and yet still celebrate words they wrote.

In his wonderful 1992 book Lincoln at Gettysburg, Garry Wills looks at the way in which one political figure in particular, Abraham Lincoln, used the Declaration of Independence to demonstrate that the U.S. Constitution was essentially an egalitarian Constitution. Lincoln was not the only one to do this. Martin Delany, who I wrote about on Juneteenth, also argued that the Declaration of Independence should be considered the Magna Carta of America, and thus the lens through which the Constitution be read and interpreted. A century later, Martin Luther King appealed to it on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, “When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir.”

Since King’s day, new schools of contemporary political philosophy have developed—some quite “liberal” and others quite “conservative”—that begin with the radically egalitarian claims of the Declaration. (These days I feel have to put “liberal” and “conservative” in scare quotes because the conservatives among us are behaving like radical destructivists while more and more liberals today are sounding like constitutional conservatives.)

For me, in this long summer of 2025, amid news of the gigantic federally mandated redistribution of wealth from the poor and young to the rich and old (as if the latter need even more), what's important about the Declaration is its articulation, from Jefferson through Delany and Lincoln to King, of a distinct and strong egalitarian tradition in American political history. Indeed, it was this tradition that helped drive the country to civil war in the 19th century, and that helped fund civil rights reforms in the 20th. There were, to be sure, plenty of hypocrites then, as there still are today (I have no doubt that the hypocrisy is somewhere in me too), but I think in an age of gross inequalities—economic, political, and civil—it is important to remember that just how central “equality” has been to the American political vocabulary and vision. Though there are those who wrongly say otherwise, the historical fact is that egalitarianism, as a creed, is a deeply American tradition. And, as Fishkin and Forbath show in their careful study in The Anti-Oligarchy Constitution, this emphasis on equality has long encompassed material economic opportunity, despite the fact that that the United States has off and on struggled to keep wealth from being captured by the few.

So, I want to leave you this Independence Day with some words from Lincoln. They were spoken in Springfield Illinois on June 26, 1857 in response to the Dred Scott ruling made a few months earlier. That ruling, as you know, announced that blacks in the United States had no rights that whites were required by law to respect. In reflecting on the ruling, Lincoln appeals to the Declaration as a bulwark against inhumanity, and as evidence that in the United States, “as fast as circumstances should permit,” the pursuit of happiness should always be linked to the pursuit of political equality and genuine economic opportunity for all:

Chief Justice Taney, in his opinion in the Dred Scott case, admits that the language of the Declaration is broad enough to include the whole human family; but he and Judge Douglas argue that the authors of that instrument did not intend to include negroes, by the fact that they did not at once actually place them on an equality with the whites. Now, this grave argument comes to just nothing at all, by the other fact, that they did not at once, or ever afterward, actually place all white people on an equality with one another. And this is the staple argument of both the Chief Justice and the Senator for doing this obvious violence to the plain, unmistakable language of the Declaration.

I think the authors of that notable instrument intended to include all men, but they did not intend to declare all men equal in all respects. They did not mean to say all were equal in color, size, intellect, moral developments, or social capacity. They defined with tolerable distinctness in what respects they did consider all men created equal—equal with “certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” This they said, and this meant. They did not mean to assert the obvious untruth, that all were then actually enjoying that equality, nor yet that they were about to confer it immediately upon them. In fact, they had no power to confer such a boon. They meant simply to declare the right, so that the enforcement of it might follow as fast as circumstances should permit.